INTRODUCTION

Minimally invasive treatments in spine surgery have significantly advanced in recent years. These procedures aim to reduce iatrogenic complications, postoperative discomfort, infection rates, and intraoperative blood loss. By preserving the posterior motion segments and paraspinal muscles, they minimize hospital stays, promote faster healing, and enable quicker return to normal daily activities. Unilateral biportal endoscopic spine surgery (UBESS) has emerged as a minimally invasive technique that has shown clinical effectiveness and safety. It has gained popularity for its potential benefits in various spinal lesions. UBESS involves 2 small incisions, providing wide and clear endoscopic visualization and causing less soft tissue damage. As an emerging endoscopic technique, UBESS offers flexibility and versatility in approaching many spinal disorders, including decompression of the spinal cord and root in the cervical or thoracic spine, as well as lumbar discectomy and spinal stenosis. Another advantage of UBESS is the ability to perform 2-handed endoscopic surgery, similar to microscopic techniques. This familiarity facilitates the adoption of endoscopic techniques and helps surgeons overcome the learning curve associated with spine endoscopy. However, there are potential complications associated with biportal endoscopic spine surgery (Table 1). A meta-analysis by Liang et al. [1] reported an overall complication rate of 5%, with dural tear being the most common complication at 2%, followed by epidural hematoma with an incidence of 1%. While the overall incidence of these complications is relatively low, it is important for clinicians to be aware of them and understand preventive methods.

COMPLICATIONS OF UBESS AND THEIR PREVENTION

1. Dura Tear

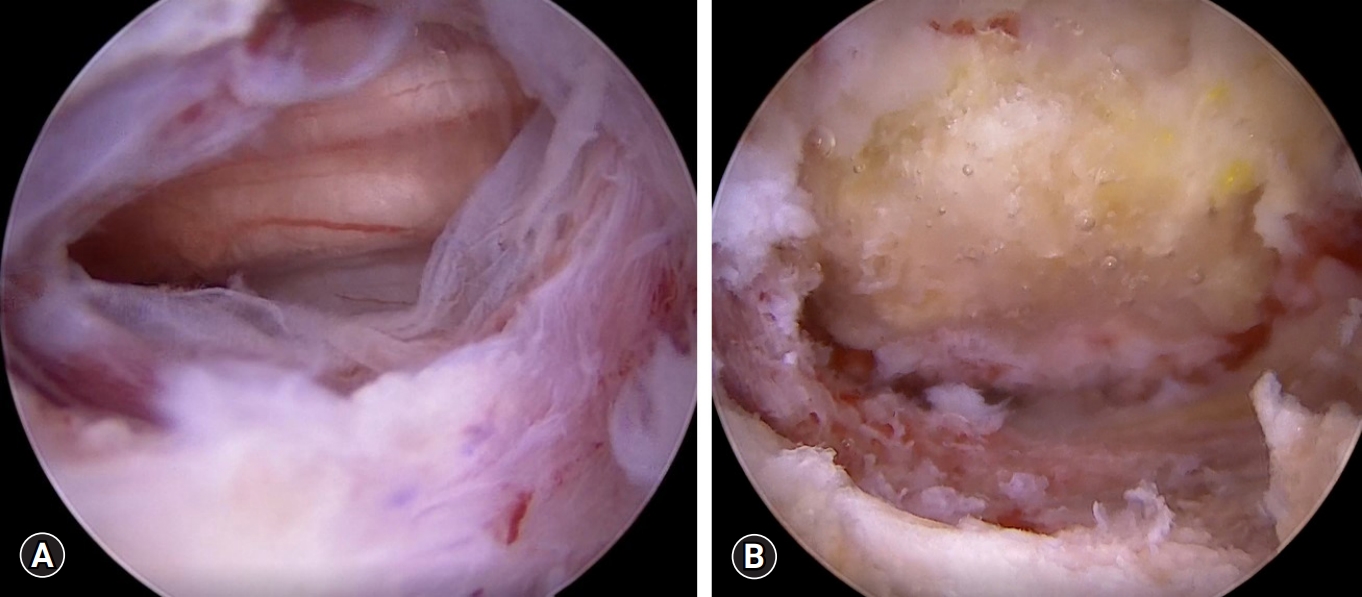

Dural tears are the most common complication in UBESS and have an incidence rate of 1.6%–14%. According to Liang et al. [1], dural injury was reported as the most common complication of UBESS for spinal stenosis, with a prevalence of 2%. During the unilateral laminotomy bilateral decompression procedure, the most common site of dural tear is the dorsal aspect of the dural sac, occurring during the removal of the ligamentum flavum [2,3]. The meningovertebral ligament, a web-like anatomical structure connecting the dura to the lamina and ligamentum flavum on the dorsal side, plays a significant role in these tears [4,5]. This ligament is predominantly located in the midline and can take the form of thin strips or thick sheets [5] Insufficient dissection of this ligament from the dura can lead to dural tears. In UBESS, while hydrostatic pressure can help separate the dural sac from the ligamentum flavum, folding can occur at the midline due to the presence of the meningovertebral ligament, potentially damaging the dural sac [1]. Lee et al. [2] suggested the use of angled curettes to remove small strips between the ligamentum flavum and dura (Figures 1, 2)

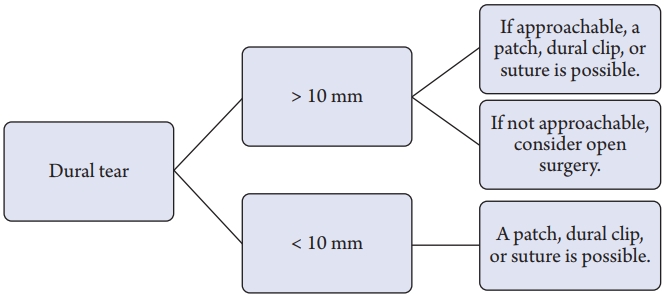

Dural tears may be associated with pseudomeningocele due to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage, surgical site infection, or rarely, meningitis. If dural repair is unsuccessful or not adequately treated, these complications can develop [6]. While open surgery typically involves primary repair as the standard treatment for dural tears, endoscopic spine surgery like UBESS does not have a standardized approach for dural tears. Kim et al. [7] proposed that small tears (<1 cm) can be effectively treated with the patch compression method, while large defects (≥1 cm) should be repaired using the dura clipping method. Choi et al. [8] suggested that minor tears (<4 mm) could be managed with bed rest alone, whereas larger tears (>12 mm) may require primary repair using a microscope (Figure 3).

2. Epidural Hematoma

Postoperative epidural hematoma is a significant complication of UBESS as it is associated with postoperative infection, epidural fibrosis, or neurological compression [9,10]. In some cases, epidural hematoma can cause problematic compression of the spinal cord or cauda equina, resulting in a significant decline in patients' quality of life. Early recognition of symptoms is crucial for determining whether further evaluation and management are necessary. Symptoms of epidural hematoma include paralysis or bladder dysfunction at the spinal cord level, as well as intractable back pain or radicular pain at the lumbar level, usually occurring within 24 hours after surgery [11]. Mild postoperative hematoma symptoms without neurological deterioration typically resolve within 3 weeks after surgery, and radiologic regression occurs spontaneously within 3 months after surgery [12]. Several factors contribute to the development of epidural hematoma, including blood pressure control, postoperative drainage, preoperative anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication, and the use of intraoperative saline infusion pumps [13]. Fujiwara et al. [14] reported that patients with hypertension and poor blood pressure control experienced a more pronounced increase in blood pressure during extubation, which could lead to bleeding. Kim et al. [15] found that high water pressure ensures clear endoscopic visualization but may conceal bleeding from epidural vessels or bone.

Electrocoagulation is a common method used to control intraoperative bleeding. However, in cases where bleeding control is unsatisfactory, hemostatic materials such as microfibrillar collagen, thrombin gelatin, and gelatin-thrombin matrix sealant can be employed. Moreover, the use of bone wax for exposed cancellous bone or the insertion of a hemovac is a useful surgical tip to prevent epidural hematoma (Figure 4).

3. Incomplete Decompression

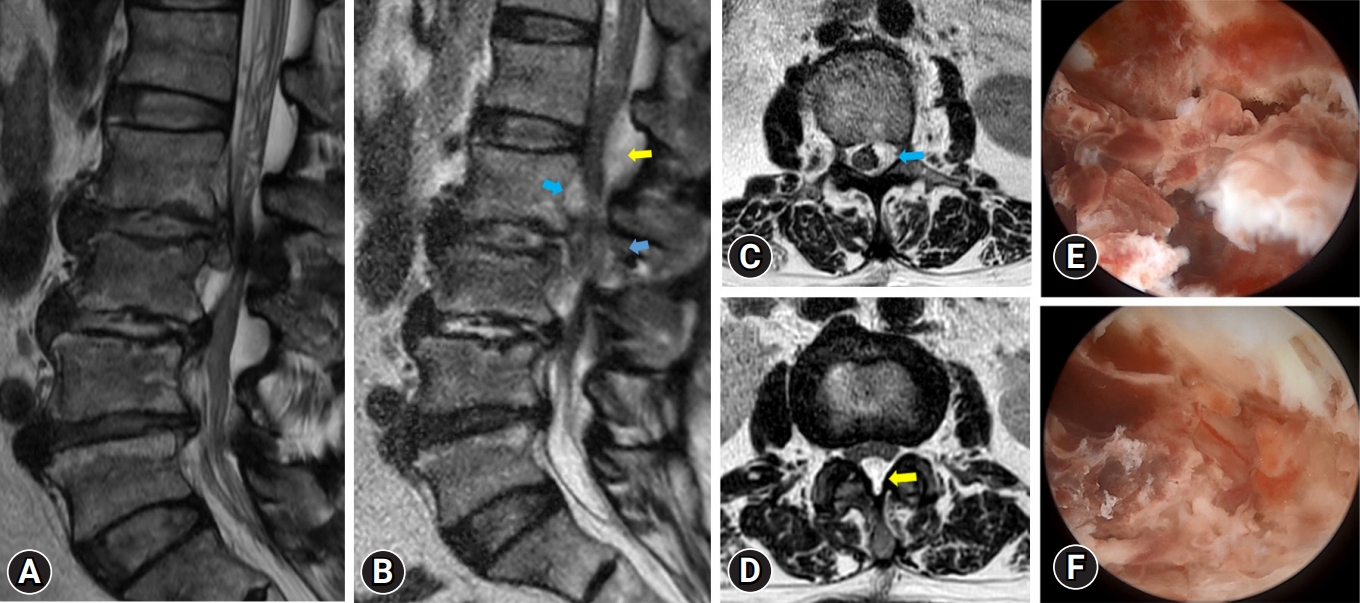

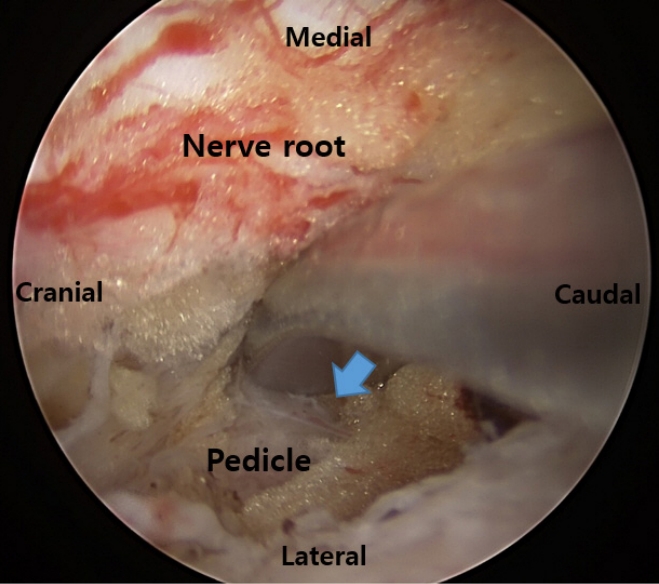

While decompression surgery with UBESS for spinal stenosis is usually excellent, in the case of severe lumbar spinal stenosis, decompression could be incomplete. Choi et al. [16] reported that inadequate resection of ligamentum flavum at the crainal and contralateral sides was related to patients experiencing radicular symptoms in their early cases. Choi et al. [16] suggested that angled curettes were more useful than Kerrison punches for performing a proper flavectomy. Angled curettes can scrape the ligamentum flavum under the lamina without requiring extensive laminectomy. To decompress the contralateral side, they recommended partial resection of the upper and lower ends of the spinous processes to create enough space for the insertion of the endoscope and instruments [16]. Moreover, the medial margin of the lower pedicle must be identified for ideal decompression of both nerve roots (Figure 5).

Blurred vision due to intraoperative bleeding can also contribute to incomplete decompression. Meticulous control of systolic blood pressure (below 100 mmHg) and the intermittent use of bone wax and gelfoam can help prevent this complication.

4. Recurrence

Recurrence after full endoscopic lumbar discectomy is associated with older age (over 50 yerars), obesity (body mass index > 25 kg/m2), higher lumbar disc herniation, and central disc herniation. Within 6 months, the disease history, Pfirrmann grade, Modic alterations, and migration grade can predict the total recurrence rate following endoscopic lumbar discectomy [17]. The aforementioned risk factors appear to be linked to recurrence of disc herniation. Soliman [18] described a case of recurrent disc herniation in a patient who had undergone UBESS.

5. Instability

Previous biomechanical investigations have found that laminectomies involving the excision of more than 50% of the pars interarticularis increase the likelihood of iatrogenic instability. Iatrogenic instability associated with UBESS could be linked to prolonged drilling of the facet joint, and excessive laminectomies are risk factors for this disorder. In a study by Kim et al. [15], the risk of iatrogenic instability was reported to be 0.6% because UBESS reduces muscle dissection and preserves the zygapophyseal joint compared to standard open surgery. In contrast, the rate of iatrogenic spondylolisthesis after open laminectomy is reported to be between 3.96% and 9.5% [19]. Iatrogenic instability can be avoided by undercutting the facet joint. It is critical to reduce facet joint infringement during surgery to prevent postoperative instability [20,21].

6. Root Injury

Radiofrequency (RF) probes are essential and widely used in UBESS. However, intraoperative thermal injury from RF has been identified as the primary cause of nerve root injury [1]. While direct contact thermal injury of the nerve root by the RF probe tip can be avoided through the surgeon's skill, indirect RF thermal injury resulting from the elevation of epidural temperature may not be entirely controlled by the surgeon [22]. Heo et al. [22] reported that RF can be safely used in UBESS, and the utilization of low-power and short-duration RF can reduce the possibility of thermal injury. Moreover, maintaining good irrigation patency in the surgical field is important for minimizing the elevation of epidural temperature caused by RF.

In UBESS, the use of a drill above the ligamentum flavum is safer than the use of a Kerrison punch to prevent root injury because ligamentum flavum can act as a barrier to protect the nerve roots during bone work.

When performing decompression at the L1/2 level, there is a possibility of spinal cord injury, particularly. Therefore, we must exercise caution to avoid compressing the thecal sac using surgical instruments such as retractors and Kerrison punches in the high lumbar segment area.

7. Infection

One notable aspect of UBESS is the absence of postoperative infection, which is a relatively common occurrence in conventional lumbar spinal surgery [23]. The incidence of spine infection after spine surgery ranges from approximately 0.1% to 4.5%, with bacterial infection being the most common cause [23]. However, UBESS has a low incidence of postoperative infection due to factors such as continuous saline irrigation, shorter operation time, and reduced soft tissue injury [24].

8. Postoperative Headache

In UBESS, the use of high intraoperative water pressure can increase CSF pressure and intracranial pressure, leading to postoperative headaches and, in severe cases, seizures [25]. Therefore, it is important to monitor patients for symptoms such as neck pain, headaches, blurred vision, and drowsiness. To prevent the occurrence of postoperative headaches, it is crucial to control intraoperative water pressure, fluid outflow, and operation time. Choi [26] advised keeping the irrigation pump pressure below 30 mmHg. Kang et al. [27] reported that cervical epidural pressure remains within the physiological range when continuous lavage is performed with an infusion pressure set to 30 mmHg. Kim et al. [28] suggested that extending the fascia incision of the working portal would be preferable to improve fluid outflow. Czigléczki et al. [29] reported that irrigation could cause meningeal irritation and postoperative headaches, but reducing the operation time can help avoid such complications.

9. Retinal Hemorrhage

After a UBE discectomy, Lee et al. [30] described a patient with retinal hemorrhage. They suggested that increased CSF pressure may have been responsible for the retinal bleeding during the unilateral biportal endoscopic (UBE) discectomy procedure. This pressure could have been transmitted to the retinal venous circulation either directly through the optic nerve sheaths or indirectly through the subarachnoid extension surrounding the optic nerve. Furthermore, higher CSF pressure has the potential to reduce cerebral blood flow, triggering a reflex increase in ophthalmic artery pressure, which can lead to capillary rupture and venous collapse. According to Lee et al. [30], it is crucial to regulate the pressure of the irrigated fluid during UBE to prevent rare complications such as postoperative retinal bleeding.

CONCLUSION

As a minimally invasive technique, UBESS has been successfully used for lumbar spine disorders and has gained popularity due to its therapeutic efficacy, including satisfactory clinical outcomes, shorter hospital stays and operation times, and lower complication rates. Based on a literature review, the most common complications of UBESS include dural tear, epidural hematoma, nerve root injury, incomplete decompression, and postoperative headache. It is crucial to have a comprehensive understanding of the procedure, surgical technique, complications, and prevention strategies associated with UBESS.