INTRODUCTION

The goal of any spine surgery is to alleviate patient’s symptoms. These goals are achieved well by conventional open surgery. However, while doing so, an efficient surgeon would always aim to minimize surgical trauma to optimize patient’s clinical and functional outcomes. Minimally invasive spine surgery came into vogue keeping this philosophy in mind without compromising the intended goal of surgery. The basic human tendency of continual advancement and the motivation to achieve better results than yesterday drives the conviction to incorporate minimally invasive spine surgery [MISS] into practice. This obviously needs to be backed with adequate evidence based studies. By virtue of utilizing soft tissue planes, muscle splitting approach, less traumatic tubular retractors and sophisticated instruments and microscopes, MISS strives to cause minimal surgical damage at every step of surgical procedure. Analysis of acute phase reactants like C-reactive protein, enzymes like creatine-phosphokinase or interleukins have shown in numerous studies that these parameters are significantly lower in less invasive procedures [1,2,4-8]. In spite of this knowledge, it becomes very challenging for a spine surgeon at any point of his career to incorporate MISS into practice.

The primary reason for this apprehension stems from the scepticism and cynicism which accompanies every new surgical technique. The anxiety to tide over the learning curve, which is steep for MISS, leads many spine surgeons to continue with the conventional approach. The additional stress associated with learning and the patience to deal with the complications encountered while embracing any new technique is a demotivating factor to embrace MISS into practice. In a world where even open spine surgery is still erroneously considered to have negative impact on patient outcomes, embarking upon MISS seems to be a task. Similarly, the reasoning that spine is not a cavity unlike abdomen and thorax which would benefit from minimally invasive procedures seems compelling enough to drive a surgeon away from MISS.

Every technique has its negative outcomes and so is true for MISS. There have been bad anecdotal examples and experiences. This puts MISS into negative light. The prime reasons behind these, we believe, is an over-zealous surgeon with extension of indications along with poor patient selection and poor surgical techniques. Mere observerships/condensed workshops or short term fellowships may not be enough to incorporate this technique. Every procedure has a learning curve which should be respected and so is true with MISS.

1. Scope of MISS

The scope of MISS is wide and incorporates most of the common surgical procedures in daily practice within its purview. Surgical procedures related to degenerative spine for herniated discs and lumbar canal stenosis with/without instability can be effectively treated with tubular retractor aided discectomy, decompression and minimally invasive transformainal lumbar interbody fusions respectively. Similarly, herniated discs in the cervical spine can be managed with tubular retractor aided laminoforaminotomy. Percutanous fixation of pedicle screws, vertebroplasty/kyphoplasty optimally treats thoraco-lumbar fractures. The scope of MISS can be broadly tabulated either for ‘access’ to the pathological site or directly address the pathology or the ‘target’ as described by Mayer et al. [10] as follows (Tables 1, 2):

Thus, it can be seen that with MISS most of the common surgical procedures in daily practice can be performed.

2. Compelling Reasons to Incorporate MISS into Practice

One of the compelling reasons to incorporate MISS into daily practice seems to be the ever growing competition amongst spine surgeons (Table 3). More and more surgeons are now using MISS techniques, which ultimately drives one to follow suit. Patients also get attracted by the glamour of MISS with smaller cosmetic surgical incisions, less post operative pain [3] and faster rehabilitation [3,9]. It is for the sake of continual surgical practice that one might have to accept MISS into his practice.

An established spine surgeon might want to reinvent his practice. Treating most surgical cases in the usual manner seems to be dull and tedious after a certain time. The passion to treat patients more effectively and the emotional drive to continually learn rekindles the spirit to learn and adopt MISS.

As opposed, an amateur surgeon may get caught unaware and MISS may be thrust upon him by his mentor during his fellowship. Thus, experiencing the outcomes of MISS could easily drive him to incorporate MISS into his practice later on.

All said and done, be it an experienced surgeon wanting to reinvent his practice or an amateur surgeon upon whom MISS is thrust upon, one of the most important compelling reasons is persistent conviction and passion which ultimately comes after accepting better clinical and functional outcomes observed after embarking upon MISS.

3. Pre-requisite for Practicing MISS

One of the pre-requisites for practising MISS is that one has to be a good ‘open’ and ‘conventional’ surgeon first. One must be thoroughly aware of all anatomical landmarks and be well acquainted with the conventional technique. It is very easy for an amateur surgeon with little experience to get disoriented intra operatively with MISS if he is not a good open surgeon first. Also, in cases of complications or worst case scenario when a surgeon is unable to execute the procedure effectively, one has to fall back to the bail out procedure and convert MISS into ‘open’ surgery. Being well exposed to open procedures helps to establish the entire peri-operative procedure at one’s finger tips and helps in step wise pushing the ‘envelope’ and thus, minimizing the learning curve associated with MISS. In conclusion, the basic principles of spine surgery remain the same and must be effectively mastered before turning to MISS.

Once a surgeon is convinced to incorporate MISS into his practice, there are numerous opportunities in doing so. This is possible at any stage of one’s surgical career, be it a beginner or an amateur surgeon or a thespian surgeon. The reasons, challenges and scope to incorporate MISS into one’s practice is however different based upon the surgical experience.

1) Beginner

The spine surgeons at the beginning of their surgical career, we consider, are the best candidates to incorporate MISS into practice. However, as mentioned early, this should be done after learning basic principles and mastering the art of conventional techniques. A beginner can pursue MISS without any inhibitions, considering there is not much in store for him to loose. A beginner usually is much more mouldable in his approach and has a tendency to absorb knowledge just like a ‘sponge’. There are plenty of opportunities for them to invest their time and energy into learning these techniques. The best guidance is provided by spending adequate time with well established surgeons who have incorporated MISS into their practice and having optimum outcomes. We do not recommend short term fellowships to master this art. Investing adequate time to overcome the learning curve and engaging in long term fellowships is the key. Surgeons at the beginning of their career have the advantage of ‘time’ to be invested in learning MISS.

Beginner surgeons would in future become the torch bearers of the field of spine surgery. Considering the widened scope and the evolution of MISS, we can say without doubt that MISS is here to stay and would broaden the horizons of spine surgery in future. Thus, a beginner surgeon with his bold attitude and consistent patience can skilfully master this technique. Intermittent pat on the back by senior surgeons and motivation by peer review will go a long way to help them to incorporate MISS into their practice.

2) Amateur

The scenario for an amateur surgeon to incorporate MISS into his practice is quite similar to a beginner surgeon. However, there are certain reasons that these surgeons would be demotivated to incorporate MISS in practice. There is plenty of ‘mental baggage’ and the fear of losing patients for the complications encountered at the beginning of their surgical career. They also have loads of investments and loans adding to the mental dilemma. However, we would suggest that passion and belief should be given the priority above everything else for ultimately reward is in store for them and there is nothing to lose.

It is very necessary for these surgeons to look at the long term ‘positives’. Though hindered by the resources of time and money unlike a beginner surgeon, it is possible for them to incorporate MISS in practice. Since these surgeons have an upper hand in understanding the basic principles and anatomy, short term fellowships and observerships with adequate guidance seem to work wonders for them. Attending workshops both simulation based and cadaver based helps in early orientation of MISS. Turning to friends and colleagues who have incorporated MISS into practice seem to best teachers in guiding them through the learning curve.

3) Thespian

The main question that comes to mind of a ‘thespian’ surgeon is ‘why’ should I incorporate MISS in practice. A thespian surgeon has gained enough stability in his surgical practice. Encountering the difficulties faced with a new technique seems detrimental to incorporate it into practice. However, it is only continued interest and passion to achieve better outcomes that can convert these ‘negatives’ into ‘positives’. The scope to learn MISS seems to be similar to an amateur surgeon through short term fellowships and workshops. However, an experienced surgeon does not have the mental baggage that an amateur surgeon faces. He has adequate patient load and thus the selection of cases is far better. One does not have to embark upon complicated cases early. Similarly, extension of indications and investment for sophisticated instruments seems to be much more feasible for an established surgeon. There is nothing to lose and considering the worst case scenario, one can covert an MISS to an open procedure.

4. Author’s Recommendation: Minimally Invasive Open Surgery

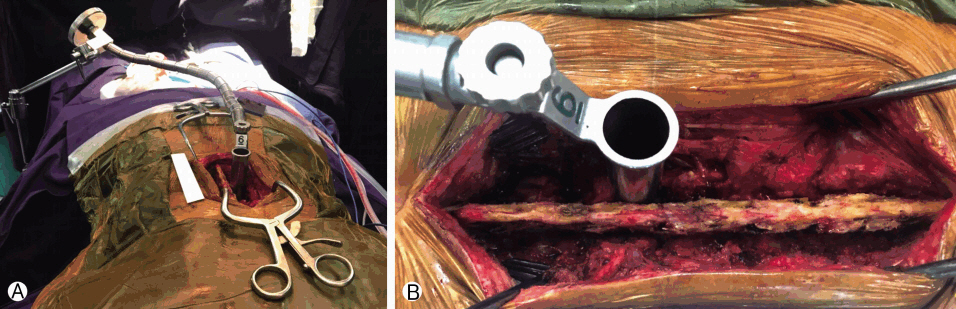

Authors would like to recommend a surgical tip where in before directly embarking upon MISS, one can have a gradual conversion from open to MISS in initial cases. For this procedure, one can expose the pathological site as done in the conventional approach. After this, one can dock the tubular retractors and reach the ‘target’ [for example, a herniated disc] and treat the pathology through the confines of the retractor. This has the advantage of allaying the anxiety and fear of MISS and orients the surgeon to the anatomy of the spine inside the tubular retractor. Similarly, if at any time intra operatively, the surgeon is not confident of delivering results, he can easily remove the tubular retractor and perform an open procedure (Fig. 1).

Having adequate training with microscopes and endoscopes and getting used to the three dimensional orientation seems to go a long way to help incorporate MISS in practice. Using sophisticated modern instruments like burrs and having anatomical orientation under the sheets is the key for MISS. Infinite patience and humility to convert to open surgery when lost helps to tide over the difficulties faced while over-coming the learning curve.

Thus, one would say that it is only the conviction that comes after observing the improved results drives a surgeon to incorporate MISS in practice. It is possible to do so at any point of one’s surgical career and there is no excuse for the same. Ample opportunities are available to learn which does require investment of adequate time, money and energy.