Full-Endoscopic Spinal Surgery for Older Patients With Degenerative Spinal Pathology: A Narrative Review

Article information

Abstract

The aging population worldwide is experiencing an increasing incidence of degenerative spinal disorders, leading to significant morbidity and diminished quality of life. Traditional open surgical approaches for treating these conditions in older patients often entail substantial risks and prolonged recovery times. However, recent advancements in endoscopic surgical techniques have provided promising alternatives with potentially reduced morbidity and quicker recovery. This paper reviews the current literature regarding full-endoscopic spinal surgery (FESS) for degenerative spinal pathology in older patients. We discuss the evolution of endoscopic techniques, patient selection criteria, surgical indications, outcomes, and complications associated with FESS in older adults. Several studies have reported favorable outcomes of FESS in older patients, including reduced postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays, faster recovery, and comparable or even improved clinical outcomes compared with traditional open surgery. Moreover, FESS offers the advantages of minimal tissue disruption, preservation of spinal stability, and decreased blood loss, which are particularly advantageous in older patients with multiple comorbidities. However, challenges such as a steep learning curve for surgeons, limited visualization, and technical constraints in managing complex pathologies remain significant concerns. Additionally, the long-term durability and effectiveness of FESS in older patients require further investigation. In conclusion, FESS presents a promising minimally invasive option for treating degenerative spinal pathology in older adults. Further research and technological advancements are needed to optimize patient selection, refine surgical techniques, and improve long-term outcomes in this growing demographic category of patients.

INTRODUCTION

The aging population worldwide presents a growing challenge in the field of spinal surgery. As life expectancy increases, the prevalence of degenerative spinal conditions among older individuals is increasing, causing a significant increase in the economic burden [1,2]. Traditional open surgical approaches have long been the standard for treating these conditions, but they often carry significant risks and complications, particularly in older patients who may have multiple comorbidities and reduced physiological reserves. The complication rate after spine surgery may be as high as 35% [3], and the recovery time is worse in older compared with younger individuals [4]. The overall quality of life frequently gets hampered after open spine surgery, and with increasing longevity nowadays, it is more of a concerning matter [5,6]. To reduce operation time and intensity of perioperative pain, hospital stay, blood loss, and infection rate, there is an increasing need for minimally invasive surgery, especially in the aging population [7].

In recent years, there has been a notable shift toward less invasive techniques in spinal surgery, driven by advancements in endoscopic technology and techniques. Full-endoscopic spine surgery (FESS) has emerged as a promising alternative to traditional open surgery, offering potential advantages such as reduced tissue trauma, shorter hospital stays, faster recovery times, and lower complication rates. Moreover, FESS can be completed under local or epidural anesthesia, thus used more easily in older patients who have multiple comorbidities, thereby reducing the complications related to general anesthesia [7,8]. With the advent of the “precise decompression” concept and continuous improvement of optical systems and endoscopic devices, the indications and intended uses of FESS have been expanded during the past 2 decades [9-11].

However, FESS in older patients presents unique considerations and challenges, and little research has been published on the issues related to this demographic. Age-related changes in spinal anatomy, diminished bone quality, and higher prevalence of comorbidities can influence surgical outcomes and patient safety. Moreover, there is a need to carefully balance the benefits of minimally invasive surgery with the potential risks in this vulnerable patient population.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the current evidence regarding FESS in older patients with degenerative spinal conditions. We will summarize outcomes compared with traditional open surgery and discuss the technical aspects of FESS, especially in the older population. By synthesizing the available evidence, we hope to offer insights into the role of FESS as a safe and effective treatment option for older patients with spinal pathologies, ultimately contributing to improved patient care and outcomes in this rapidly growing demographic.

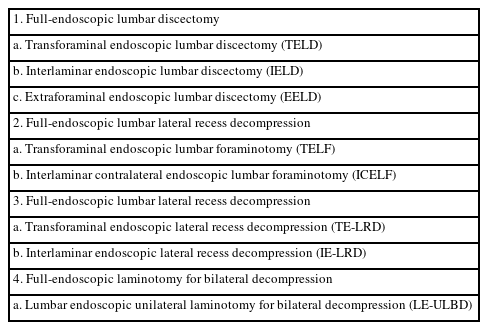

AOSpine ENDOSCOPIC SPINE SURGERY NOMENCLATURE SYSTEM

With the development of endoscopic lumbar surgery, a heterogeneous nomenclature system defines endoscopic procedures, which causes confusion between endoscopic surgeons and patients. Recently, the AOSpine group published a consensus paper on nomenclature for working-channel endoscopic procedures (Table 1) [12]. Thus, to improve communication, we used the nomenclature recommended by the AOSpine group in this review.

CLINICAL AND PHYSIOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF OLDER PATIENTS WITH DEGENERATIVE LUMBAR SPINAL DISEASES

Older patients with degenerative lumbar spinal disease often present with unique clinical and physiological characteristics and considerations compared with younger patients. Thus, managing degenerative lumbar spinal disease in older patients presents distinctive challenges due to age-related physiological changes, comorbidities, and potential complications. When considering treatment options for these patients with symptomatic spinal disease, several crucial factors should be taken into account, such as life expectancy, the ability to tolerate surgery, and overall health.

Assessing the life expectancy of older patients is vital in determining the potential benefits and risks of surgical intervention. If a patient has a limited life expectancy because of age or other health issues, conservative management or less invasive procedures may be preferred over surgical procedures with prolonged recovery periods. Older patients may have decreased physiological reserves and have multiple comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and osteoporosis [13,14]. These conditions may influence their ability to tolerate surgical intervention and impact their postoperative recovery, significantly increasing the risk of perioperative complications such as infections, thromboembolic events, and delirium. According to Cloyd et al. [5], the complication rates for spinal surgery in older patients range from 10% to 67%. However, differences in patient population, indications for surgery, and operative details, as well as variations in the definition of “complication,” make comparing these data difficult. Hence, the benefits and risks of surgery must be carefully considered in older patients. Moreover, choosing an appropriate surgical approach and conducting preoperative risk assessments are crucial to successful outcomes after spinal surgery.

Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) in older patients is characterized by degenerative changes such as facet joint hyperplasia and ligamentum flavum hypertrophy. In most cases, multiple segments are involved, and lumbar spondylolisthesis and scoliosis are observed. However, the symptoms of nerve injury are often inconsistent with imaging findings, and the location of the affected segments is unclear. Therefore, for older patients with LSS, the goal of surgical treatment is to completely decompress while maintaining spinal stability. Moreover, depending on the patient’s physiological condition, reducing anesthesia and operation time and minimizing surgical trauma is important. While traditional open surgical treatment can achieve extensive decompression and pain relief, it takes a long time for patients to resume normal activities and improve their quality of life. With the continuous advancement and development of FESS, studies show that FESS is safe and effective in terms of low blood loss, minimal postoperative wounding, minimal nerve adhesions, minimal impact on the stability of the posterior spine, fast postoperative recovery, and the option of local anesthesia [10,15].

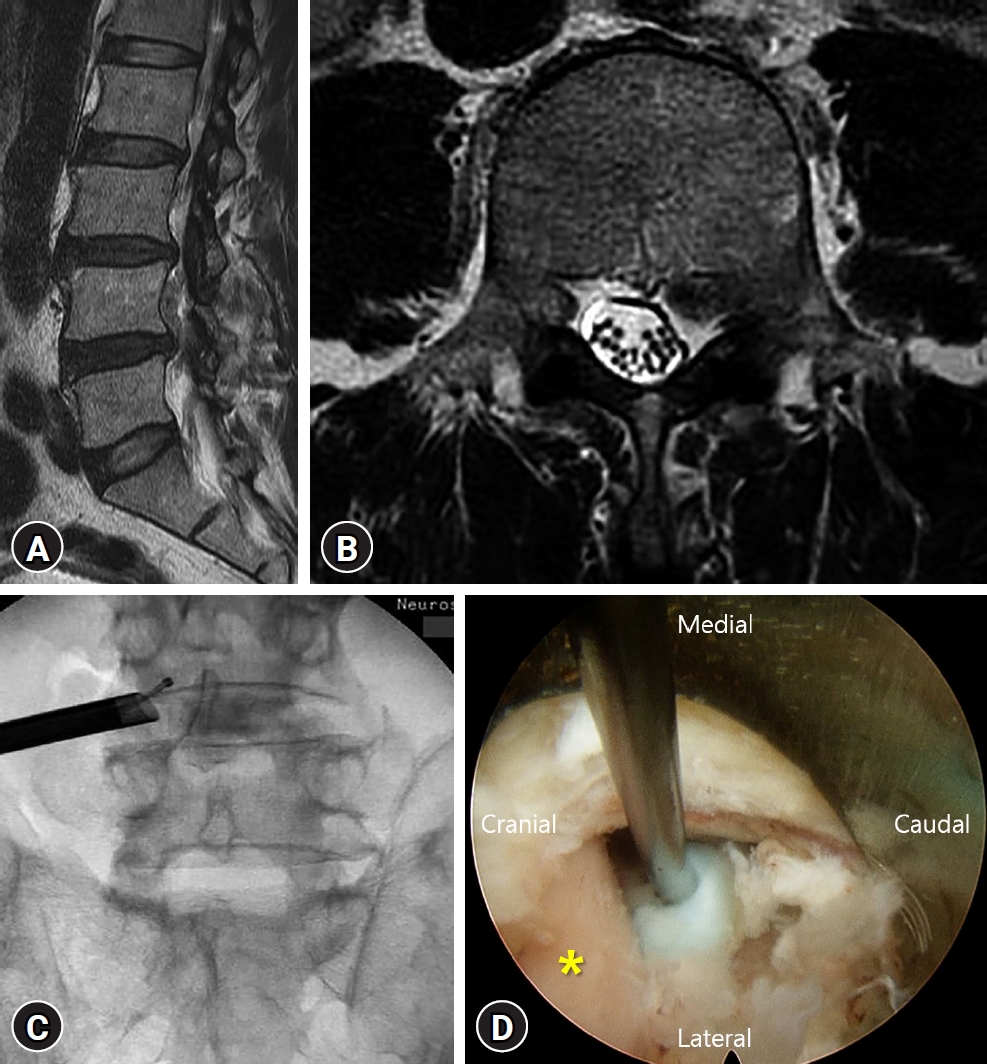

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 76-year-old man visited our Emergency Department complaining of lower back pain and severe radiating pain to the left leg. He could not walk because of the radiating pain. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a ruptured and upward migrated disc compressing the L4 nerve root (Fig. 1A and B). He had multiple comorbidities, including hypertension, chronic renal failure, and diabetes, and was operated on for coronary stent insertion recently. We first tried a selective nerve root block for the left L4 root. However, the radiating pain was not improved, and he complained of weakness and numbness in the left leg. We planned to perform a transforaminal endoscopic lumbar discectomy (TELD) instead of a conventional open microdiscectomy. With the transforaminal endoscopic approach, we found and removed the migrated disc material safely (Fig. 1C and D). The visual analogue scale (VAS) score for the leg was improved from 9 to 3 immediately after TELD. The day after TELD, the patient was discharged without any complications. Six months postoperatively, he reported a VAS score of 2 for the leg. We got an informed consent about this study from the patient.

FESS ADVANTAGES

FESS offers several advantages over conventional open surgery, particularly for older or medically compromised patients who may be at higher risk for complications associated with extensive procedures under general anesthesia [16]. Some of the key advantages include:

1. Minimized Tissue Trauma

FESS involves smaller incisions than open surgery, reducing damage to surrounding tissues such as muscles, ligaments, and blood vessels [17]. This can lead to less postoperative pain and faster recovery.

2. Preservation of Segmental Stability and Mobility

Endoscopic techniques allow for targeted access to the affected area of the spine while preserving the surrounding structures [18]. This helps maintain segmental stability and mobility, which is crucial for overall spinal function. By opting for endoscopic techniques, fusion surgery can be avoided.

3. Reduced Blood Loss

The minimally invasive nature of FESS typically results in less intraoperative bleeding compared with traditional open procedures [19]. This can reduce the need for blood transfusions and lower the risk of associated complications, especially in older adults.

4. Shorter Operation Time and Hospital Stay

FESS often requires less time in the operating room and can be performed on an outpatient basis or with shorter hospital stays than open surgery [19]. This can lead to quicker recovery and a faster return to normal activities.

5. Local Anesthesia and Conscious Sedation

Endoscopic procedures can often be performed under local anesthesia combined with conscious sedation, eliminating the need for general anesthesia in many cases [19]. This reduces the risks associated with anesthesia and can be particularly beneficial for older patients or those with underlying medical conditions.

6. Less Postoperative Medication

With reduced tissue trauma and pain, patients undergoing endoscopic spine surgery may require less postoperative pain medication compared with those undergoing open surgery. This can minimize side effects and improve overall patient comfort during the recovery period.

7. Fewer Wound Complications

The smaller incisions used in FESS may result in fewer wound complications such as infection, wound dehiscence, and delayed wound healing compared with open procedures.

8. Quicker Return to Regular Activities:

The combination of reduced tissue trauma, shorter operation time, and faster recovery may allow patients to return to their regular activities sooner after endoscopic spine surgery compared with traditional open procedures.

Overall, FESS offers a practical alternative for older or medically compromised patients who may not be suitable candidates for extensive open surgery under general anesthesia. Endoscopic surgery may reduce surgical morbidities or complications, especially in older or medically compromised patients.

ROLE OF FESS IN OLDER PATIENTS WITH VARIOUS SPINAL DISEASES

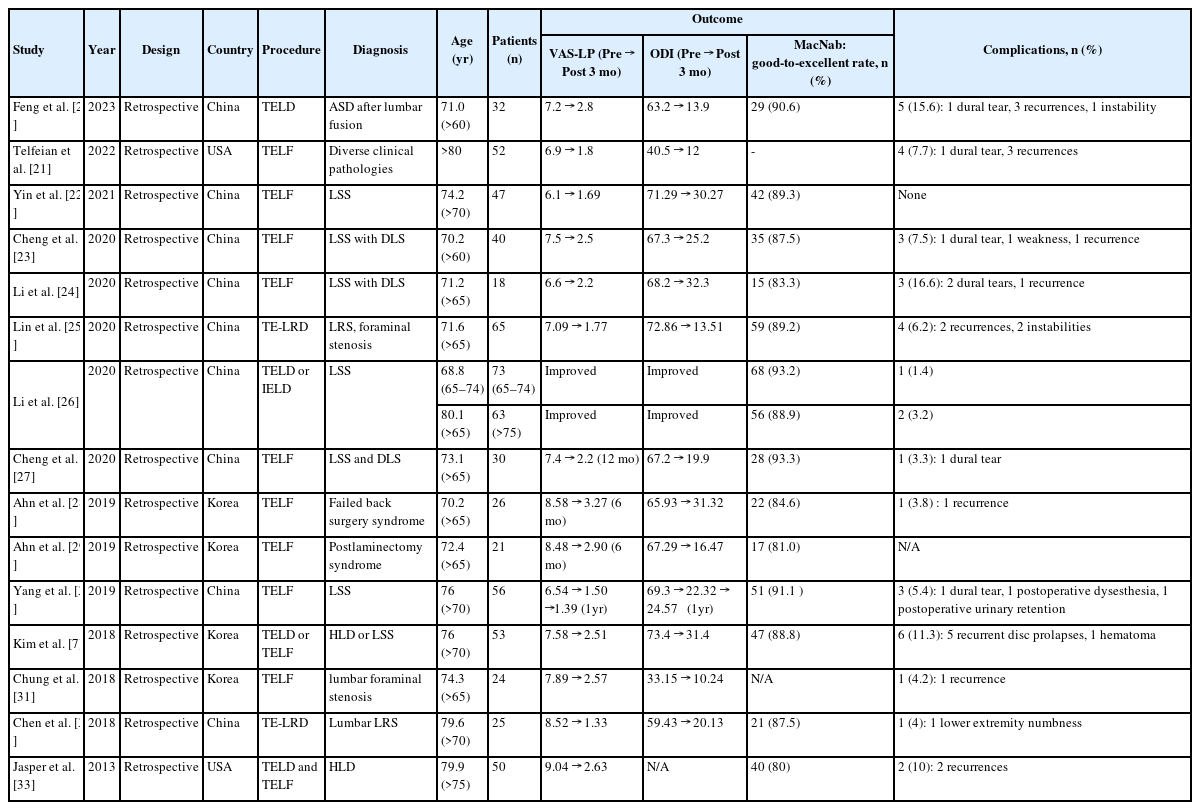

1. Efficacy and Safety of FESS in Older Adults

Although many articles show the clinical efficacy and safety of FESS, few studies report these aspects in older patients. We summarized the results of these articles in Table 2 [7,20-33]. Many authors proved good clinical efficacy by showing clinical improvement in the VAS, Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scores, and MacNab criteria after FESS in different spinal pathologies. Kim et al. [7] reported the results of endoscopic surgery (TELD or transforaminal endoscopic lumbar foraminotomy [TELF]) in older patients with degenerative lumbar spine disease. As shown in Table 2, VAS and ODI scores were significantly improved after endoscopic surgery, and a good-to-excellent outcome on MacNab criteria was noted in 47 patients (88.8%, 47 of 53). Five patients (9.4%, 5 of 53) developed recurrent disc prolapse, and 1 patient developed hematoma with motor weakness, which required open irrigation. They suggested that despite recurrence as the most common complication, FESS is pivotal in addressing old age degenerative spine disease without exposing patients to more extensive open surgery. In 2020, Lin et al. [25] also reported the clinical results of endoscopic spine surgery (transforaminal endoscopic lateral recess decompression [TE-LRD]) in older patients with lumbar lateral recess and foraminal stenosis. They evaluated the efficacy and safety of this procedure. Leg VAS and ODI scores were significantly lower compared with preoperative scores (Table 2). Good or excellent results in MacNab criteria were obtained in 89.23% (59 of 65) of the patients. Regarding the complications, 2 patients developed recurrent disc protrusion, and 2 patients underwent fusion owing to recurrent spinal canal stenosis combined with instability. Based on these clinical observations, they suggested that TE-LRD is a safe and reliable technique for treating lumbar lateral recess stenosis and foraminal stenosis in older patients.

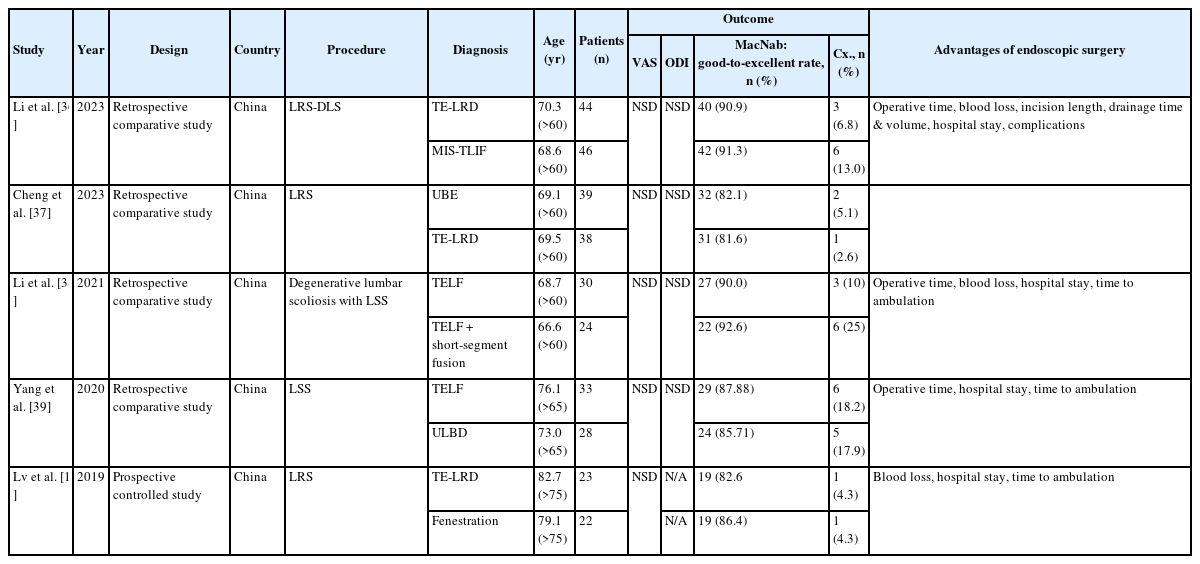

2. Comparing FESS With Open Surgery in Treating Older Patients With Lumbar Degenerative Diseases

Many reports exist regarding the clinical efficacy and safety of percutaneous spinal endoscopy versus traditional open surgery for several lumbar spinal diseases [18,34,35]. However, only a few studies compare FESS and open surgery in older patients (Table 3) [10,36-39]. As shown in Table 3, the clinical results of FESS, calculated by VAS, ODI, and MacNab criteria, were not significantly different between FESS and open surgery in all the studies included. However, FESS was advantageous in terms of the operation time, estimated blood loss, incision size, length of hospital stay, and time to ambulation compared with conventional open surgery.

Comparison of FESS with open surgery in the treatment of older patients with lumbar degenerative diseases

Yang et al. [39] compared the safety and efficacy of full-endoscopic and microscopic unilateral laminotomy for bilateral decompression for LSS in older patients. Both Full-endoscopic and microscopic decompression have achieved favorable clinical results in treating older patients with LSS, and the complications are minor (Table 3). Thus, they suggested that full-endoscopic decompression has the advantages of a small incision and rapid recovery, which can be used as an alternative for treating LSS, especially for older individuals with comorbidities. Recently, Li et al. [36] compared the safety and short-term clinical efficacy of TELF under local anesthesia and minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (MIS-TLIF) in treating lateral recess stenosis associated with degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis (LRS-DLS) in patients over 60 years old. In their study, TELF and MIS-TLIF led to favorable outcomes in geriatric patients with LRS-DLS. In addition, TELF caused less severe trauma and fewer complications. Accordingly, they suggested that regarding perioperative quality of life and clinical outcomes, TELF could supplement MIS-TLIF in geriatric patients with LRS-DLS.

3. Comparing FESS Outcomes Between Older and Younger Patients With Lumbar Herniated Discs

As we mentioned above, several studies have suggested that endoscopic spinal surgery reduces perioperative complications and hospital stays compared with traditional open surgery, especially in older individuals. However, some authors have reported that advanced age is a risk factor for recurrence and reoperation after FESS [40,41].

To address this controversy, Son et al. [42] recently compared the outcomes of FESS between older and younger patients with herniated discs in the lumbosacral region. In their study, patients were allocated to 2 groups: a young group aged ≤65 years (n=202) or an older group aged >65 years (n=47). The overall outcomes, including pain improvement, radiological change, operation time, blood loss, and hospital stay, were not different between the 2 groups. Furthermore, the perioperative complication rates (9 patients [4.46%] in the young group and 3 patients [6.38%] in the older group, p=0.578) and adverse events over the 3-year follow-up period (32 patients [15.84%] in the young group and 9 patients [19.15%] in the older group, p=0.582) were comparable between the groups. They suggested that FESS produces similar outcomes in older and younger patients with a herniated disc in the lumbosacral region. FESS can be considered a safe option for appropriately selected older patients.

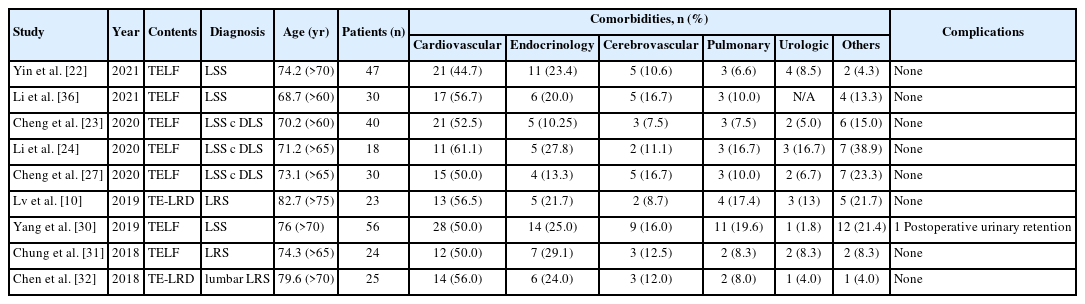

THE INCIDENCE OF PERIOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS OF FESS IN OLDER PATIENTS WITH COMORBIDITIES

As we mentioned above, FESS offers a practical alternative for elderly or medically compromised patients who may not be suitable candidates for extensive open surgery under general anesthesia. Using this endoscopic surgery, the surgical morbidities or complications may be reduced especially in the older or medically compromised patients. We summarized the prevalence of comorbidities among the older patients who underwent FESS and the incidence of perioperative complications related comorbidities after FESS (Table 4). The prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidity was relatively high (44.7%–61.1%) in older patients. However, the incidence of perioperative major complications, including neuro-vascular injury, thrombophlebitis, or surgical wound infection was very low. In most of the literature, no complication was reported after FESS in older patients with multiple comorbidities. Only 1 case of transient postoperative urinary retention was reported after FESS [30]. Because FESS can be done under local anesthesia and decrease the invasiveness with which the spine is approached, we may avoid perioperative complications even in older patients with multiple comorbidities. Therefore, FESS is useful option in treating older patients with comorbidities.

PATIENT SELECTION IN ENDOSCOPIC SPINE SURGERY AMONG THE OLDER PATIENTS

Patient selection for endoscopic spine surgery among older patients requires special consideration due to age-related factors and potential comorbidities. Here are some key points to consider:

1. Overall Health Status

Older patients often have multiple comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or osteoporosis. The patient's overall health status and ability to tolerate surgery and anesthesia should be carefully evaluated [43].

2. Frailty Assessment

Frailty assessment tools can help determine the physiological reserves and functional capacity of the older patients. Frail patients may be at higher risk for surgical complications and may require additional preoperative optimization or postoperative care [43].

3. Cognitive Function

Cognitive function should be assessed to ensure that patients have the capacity to understand the risks and benefits of surgery and provide informed consent. Patients with significant cognitive impairment may not be suitable candidates for endoscopic spine surgery.

4. Bone Density

Osteoporosis is common among the older patients and can affect bone quality, which may impact the feasibility of endoscopic spine surgery. Preoperative assessment of bone density and optimization of bone health may be necessary to reduce the risk of vertebral fractures during surgery [44].

5. Severity of Symptoms

The severity of spinal symptoms and functional impairment should be carefully evaluated in older patients. Surgery may be recommended for patients with debilitating symptoms that significantly affect their quality of life and are refractory to conservative treatments.

6. Surgical Goals

Clear surgical goals should be established based on the patient's symptoms and imaging findings. Endoscopic spine surgery may be appropriate for decompression of neural structures or removal of herniated discs in older patients with symptomatic spinal pathology.

7. Minimally Invasive Approach

Endoscopic spine surgery offers the advantages of minimally invasive techniques, including smaller incisions, reduced blood loss, and faster recovery times, which may be particularly beneficial for older patients who may have slower wound healing and prolonged recovery.

8. Multidisciplinary Evaluation

A multidisciplinary team approach involving geriatricians, spine surgeons, anesthesiologists, and other specialists may be necessary to comprehensively evaluate the older patients for endoscopic spine surgery and optimize perioperative care.

9. Patient Preferences and Goals of Care

Patient preferences, goals of care, and expectations should be carefully considered in the decision-making process. Shared decision-making between the patient, their family members, and the healthcare team is essential to ensure that treatment aligns with the patient's values and preferences.

10. Postoperative Rehabilitation and Support

Older patients may benefit from comprehensive postoperative rehabilitation and support services to optimize functional recovery and minimize the risk of complications such as falls or pressure ulcers during the recovery period.

By considering these factors and individualizing treatment plans based on the specific needs and characteristics of the older patients, surgeons can optimize the safety and effectiveness of endoscopic spine surgery in this population.

FESS LIMITATIONS OR DISADVANTAGES IN OLDER PATIENTS.

While FESS offers numerous advantages, it is essential to recognize and address the associated risks and limitations, particularly for beginner surgeons and older patients [45]. Limitations or disadvantages also exist related to endoscopic spine surgery.

1. Complications

Despite advancements, FESS can still be associated with complications such as dysesthesia (abnormal sensation), epidural hematoma, nerve root injury, dural tear, and surgical site infection [46,47]. To avoid postoperative dysesthesia, minimal dorsal root ganglion involvement is important. Kim et al. [48] showed the interlaminar contralateral approach has a lower postoperative dysesthesia rate than TELD. Regarding the dural tear, Lewandrowski et al. [49] performed a study among endoscopic spine surgeons via social networking and reported a 1.07% dural tear incidence (689 dural tears in 64,470 lumbar endoscopies). However, the absolute incidence of a cerebrospinal fluid fistula was only 0.025% (16 fistulas in 64,470 endoscopies ). Increased radiation exposure is also inevitable during endoscopic spine surgery [16]. Moreover, reoperations were needed in several cases because of remnant or recurred discs. Even in experienced hands, some herniations remain technically difficult. According to the literature, huge central and highly migrated disc herniations showed a high failure rate [50,51]. Thus, surgeons should consider the possibility of these complications prior to endoscopic spine surgery.

2. Learning Curve

FESS requires a significant learning curve, and beginner surgeons need extensive training and experience before performing surgeries independently. Studies suggest a surgeon may need at least 10 to 20 cases to achieve proficiency [52]. Hsu et al. [53] revealed similar findings where the plateauing of the learning curve for the transforaminal approach occurred around the 10th case. In addition, most studies have an explicit limitation in suggesting the cutoff values of the initial 20 cases through comparison between random groups dichotomized based on the operation time [54]. The learning curve can be steep and challenging owing to the complex anatomy and technical skills required for endoscopic procedures.

3. Limited Feasible Indications

While the indications for FESS have expanded, there are still limitations on the types of cases suitable for this approach. Conditions such as extensive migrated disc herniation, calcified discs, severe central spinal stenosis, nerve root anomalies, cauda equina syndrome, and severe fibrotic tissue adhesions may not be appropriate for FESS. Additionally, older patients may have advanced pathological conditions, further restricting the feasible indications for endoscopic surgery [55,56]. Moreover, multiple-level pathologies and an L5–S1 level with a high iliac crest are contraindications of endoscopic surgery. Therefore, careful preoperative evaluation and appropriate patient selection are essential prerequisites to lowering the risk of FESS complications.

4. Complex Cases

Some types of disc herniations, particularly huge central or highly migrated herniations, may present technical challenges and have higher failure rates with endoscopic techniques. Surgeons must carefully evaluate each case to determine the suitability of FESS and be prepared for the possibility of conversion to open surgery if needed.

CONCLUSIONS

Older patients often have comorbidities and age-related physiological changes that can affect surgical outcomes and recovery. Factors such as osteoporosis, decreased mobility, and increased anesthesia risks need to be carefully evaluated when considering spine surgery in this demographic. FESS in older patients highlights its potential benefits and challenges. While FESS offers advantages such as reduced tissue damage, shorter hospital stays, and quicker recovery times, it also presents unique considerations in the older population. Based on the literature review, evidence suggests that FESS can be safely performed in older patients with appropriate patient selection, meticulous surgical technique, and comprehensive perioperative care. Moreover, studies have shown promising outcomes in terms of pain relief, functional improvement, and patient satisfaction. However, further research is needed to better understand the long-term efficacy and safety of endoscopic spine surgery in older patients.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.