Strengths and Merits of Transforaminal Full-Endoscopic Lumbar Spine Surgery Under the Local Anesthesia: A Review Article

Article information

Abstract

In the 2 decades or so since full-endoscopic spine surgery (FESS) was introduced, the procedure has advanced considerably. There are 2 major approaches of FESS, transforaminal (TF) and interlaminar. In this review article, we discuss the key strengths and merits of TF-FESS based on a literature search. First, the minimal invasiveness of the procedure allows for early return to work. Second, minimal invasiveness of the back muscles enables athletes to make a faster return to their previous competitive level. Third, the ability to perform TF-FESS under local anesthesia means it is suitable even in the elderly with poor general health.

INTRODUCTION

Full-endoscopic spine surgery (FESS) was first performed around the end of 20th century [1-3] and has advanced considerably over the past 2 decades. There are 2 major approaches of FESS, transforaminal (TF) and interlaminar (IL). TF-FESS accesses the intervertebral disc space and the spinal canal via Kambin triangle [4,5], whereas IL-FESS accesses them via the IL space [6-8]. While IL-FESS has become the minimally invasive option for traditional posterior surgery such as Love’s herniotomy and laminectomy under general anesthesia, advancements of TF-FESS have markedly increased its indications.

TF-FESS originated with the technique of trans-Kambin triangle percutaneous nucleotomy (PN) [9], and its indications expanded after a spinal endoscope was used for PN. Initially, TF-FESS was performed for discectomy [1-3]. With advancements in instrumentation, decompression of lumbar spinal canal stenosis became possible [10-12] and, more recently, TF-FESS using trans-Kambin lumbar interbody fusion was developed [13-19]. Importantly, because the full endoscope can be inserted through Kambin triangle, TF-FESS is also indicated for intradiscal surgery, which would be very difficult to perform with IL-FESS. TF-FESS is therefore also used to treat discogenic pain [20-22] and type 1 Modic change [23,24].

Based on a literature search, in this review article we discuss 3 key strengths and merits of TF-FESS, namely, early return to work (RTW), early return to sports (RTS) activity at the previous competitive level in athletes, and suitability for the elderly in poor general health.

METHODS

1. Early RTW

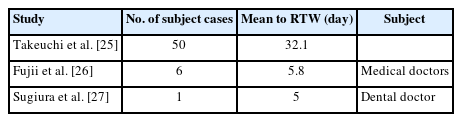

The minimally invasive nature of TF-FESS allows patients to make an early RTW [25-30]. In a review of 50 cases by Takeuchi et al. [25], the mean RTW duration was 32.1 days after TF-FESS (Figure 1). The median duration of was 21.0 days, indicating that half of the patients could return to work within 3 weeks. Interestingly, 25% of cases returned within a week. Takeuchi et al. [25] concluded that TF-FESS enables patients to have an early RTW compared with traditional open surgery. Fujii et al. [26] analyzed the RTW duration after TF-FESS in 6 patients who were medical doctors. The mean RTW duration was 5.8 days, which was earlier than for Takeuchi et al. [25]’s patients. Five of the 6 medical doctors returned to their clinical duties within a week, with the remaining doctor, who was a resident, able to take a longer period of sick leave. Sugiura et al. [27] also reported early return after full-endoscopic ventral facetectomy for lumbar spinal lateral recess stenosis. Their patient was a 60-year-old dentist who was able to return to work within just 5 days after the surgery (Table 1). The effectiveness of TF-FESS for early RTW has also been reported in another clinical study, a clinically oriented review paper, and a prospective randomized controlled trial [28,29,30].

Quick return to previous work after transforaminal full-endoscopic spine surgery. The median duration of 50 cases was 21.0 days, indicating that half of the patients could return to previous work within 3 weeks.

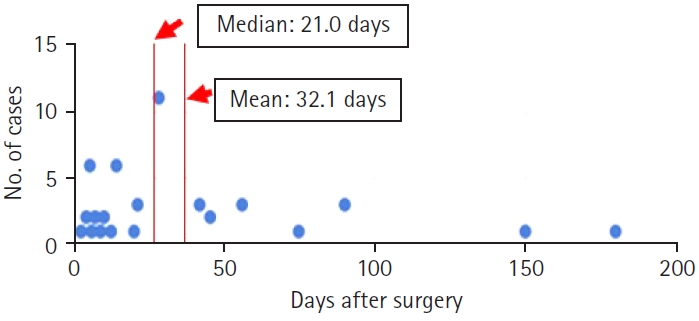

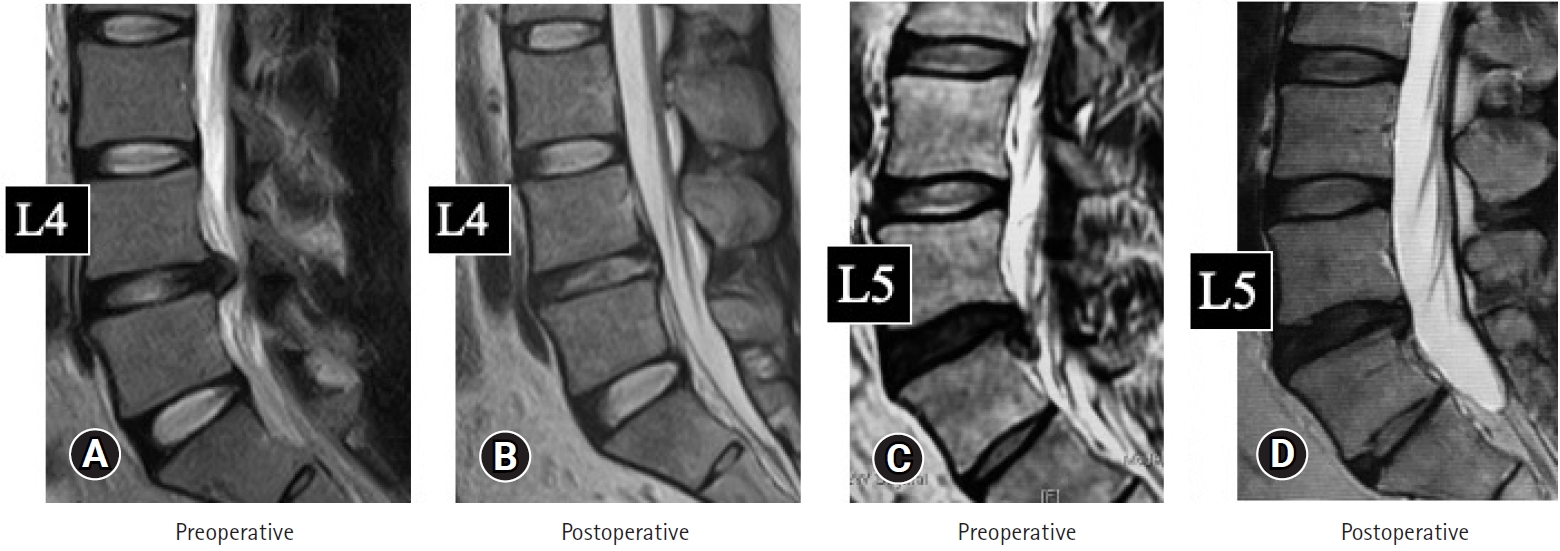

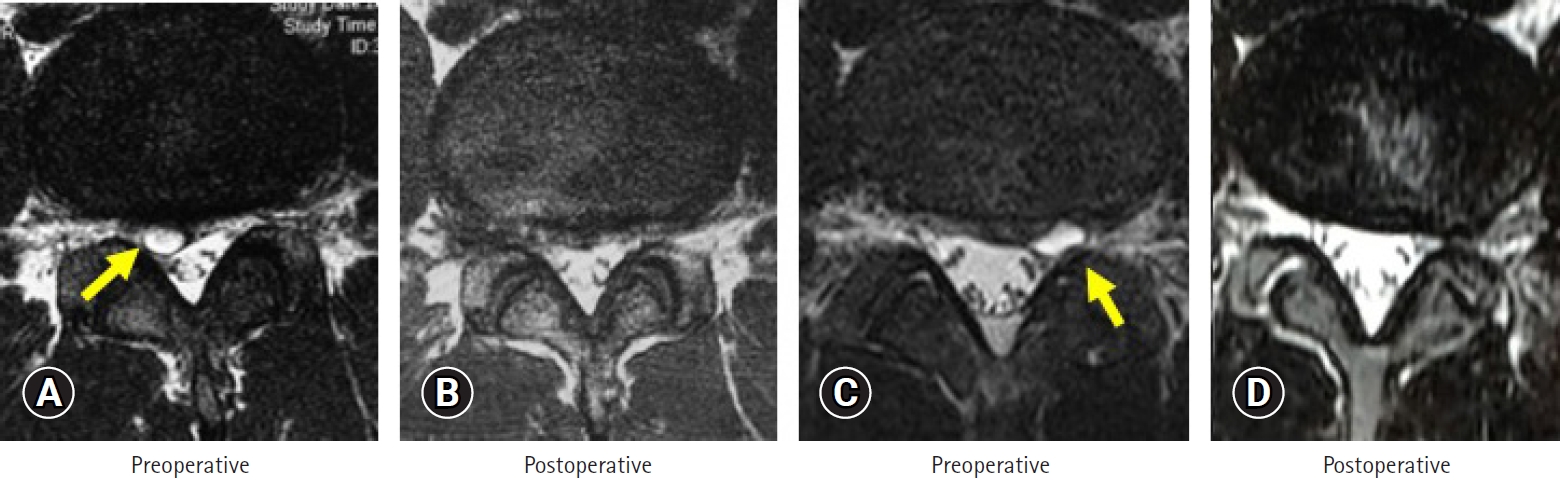

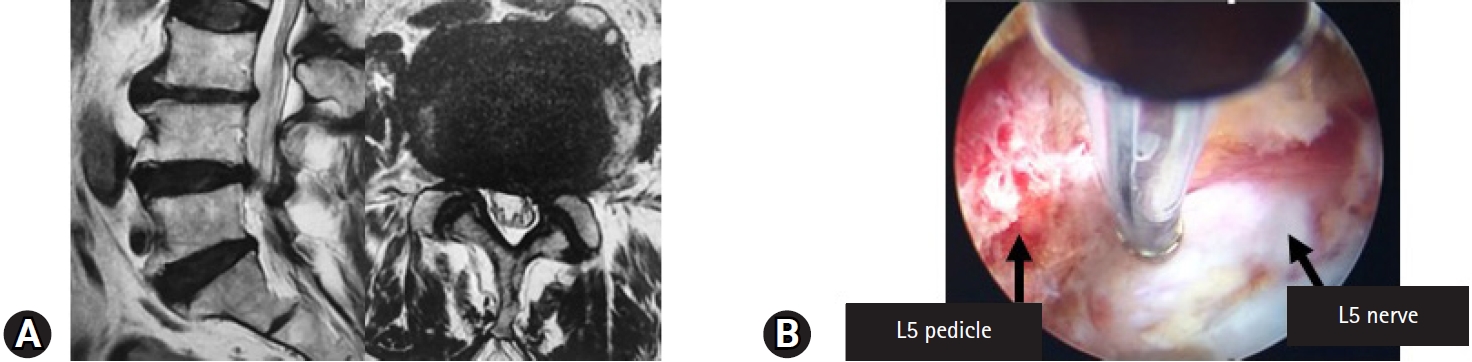

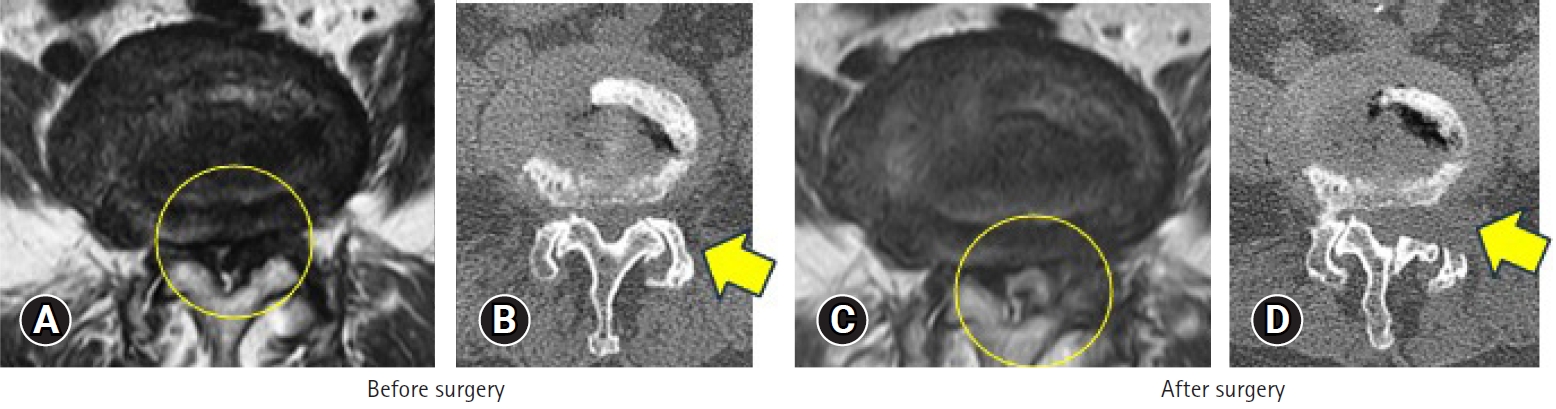

TF-FESS was performed to treat 2 medical doctors with herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP), to enable early RTW. As shown in Figure 2, the HNP in each case was successfully removed by TF-FESS under local anesthesia. Both doctors returned to work within a week, 5 days in case 1 and 6 days in case 2. There was no recurrence of HNP during 2 years of follow-up. In addition, we treated a patient with bilateral lumbar lateral recess stenosis. He underwent bilateral full-endoscopic ventral facetectomy under local anesthesia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans after the surgery clearly showed neural decompression, and computed tomography (CT) scans showed bony decompression (arrows, Figure 3). He returned to his previous work only 5 days after the surgery.

(A, B) Case 1: 32 years old. (C, D) Case 2: 42 years old. Pre- (A, C) and postoperative magnetic resonance images (B, D) for 2 medical doctors with HNP. The HNPs were successfully removed by TF-FESS under local anesthesia in both cases and they returned to work within 5 and 6 days, respectively. HNP, herniated nucleus pulposus; TF-FESS, transforaminal full-endoscopic spine surgery.

Pre- (A) and postoperative imaging (B) findings in a male patient with bilateral lumbar lateral recess stenosis. After full-endoscopic ventral facetectomy under local anesthesia, MRI clearly indicates neural decompression and CT scan shows bony decompression (arrows). CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

2. Early Return to Previous Sports Activity in Athletes

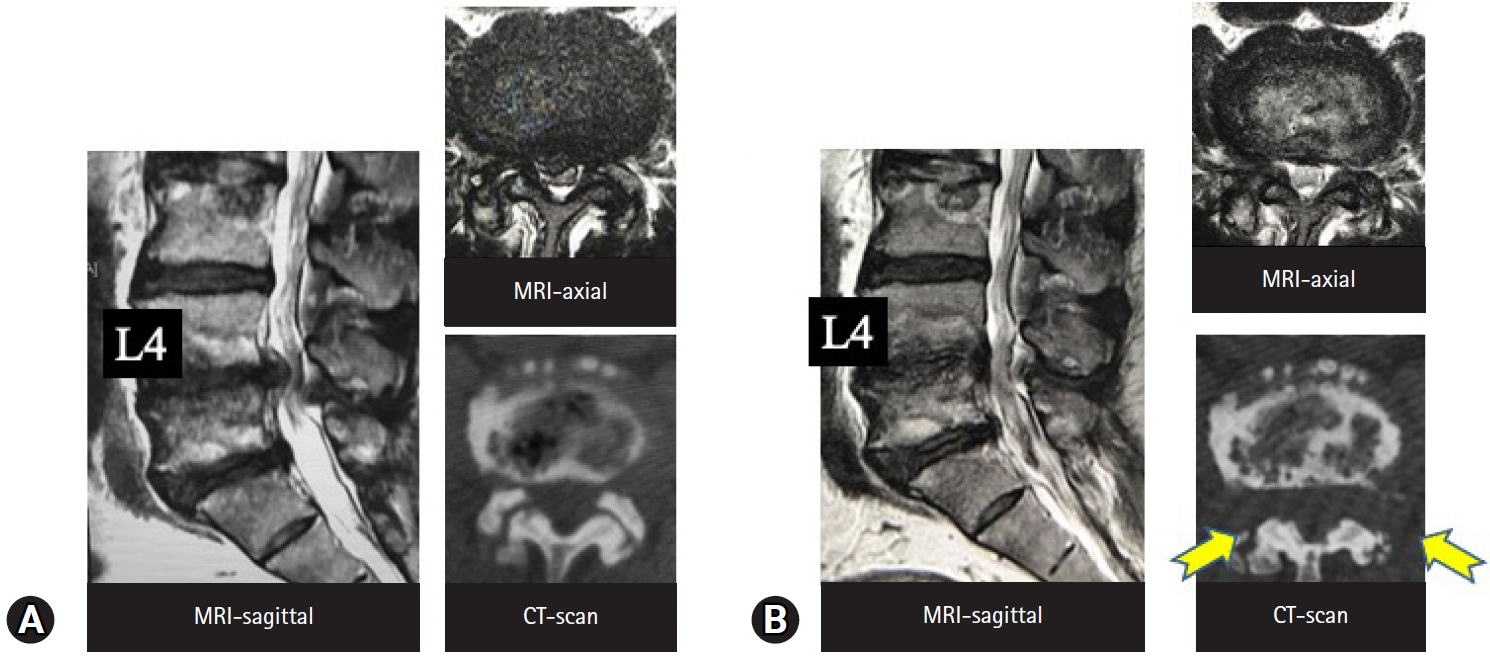

The minimal invasiveness of the back muscles with TF-FESS allows athletes to make a faster return to their previous competitive level [31-35]. HNP is the major surgical indication for the procedure among athletes. Yamaya et al. [31] reviewed 18 cases of HNP in high-school athletes, all of which were treated successfully with full-endoscopic discectomy. Seventeen of the 18 athletes (94.4%) made a full RTS, and the mean RTS duration was 7 weeks. The authors concluded that TF-FESS is effective for surgical treatment of HNP in adolescent athletes. Discal cyst is another pathology involving the intervertebral disc [32,33]. In 2015, Jha et al. [32] reported full-endoscopic surgical resection of a discal cyst for high-school baseball pitcher. Using the inside-out technique, they removed HNPs as well as the ventral wall of the discal cyst, completely resolving his low back and leg pain and enabling an early RTS. Takamatsu et al. [33] described their TF-FESS technique to meticulously remove a discal cyst in a professional baseball player. They used the outside-in technique described by Yoshinari et al. [36]. Following foraminoplasty, they could see the lateral wall of the cyst and ruptured it using bipolar pulsed radiofrequency. They then removed an HNP and the ventral wall of the cyst from inside the disc space. The RTS duration was 3 months after the TF-FESS. Figure 4 shows the MRI scans of 2 representative cases of discal cyst [32,33] that were successfully treated by TF-FESS.

(A, B) Case 3: 18 years old. (C, D) Case 4: 22 years old. Pre- (A, C) and postoperative magnetic resonance image (B, D) findings in 2 representative cases of discal cyst. The cysts were resected successfully by transforaminal full-endoscopic spine surgery technique in both cases (arrows).

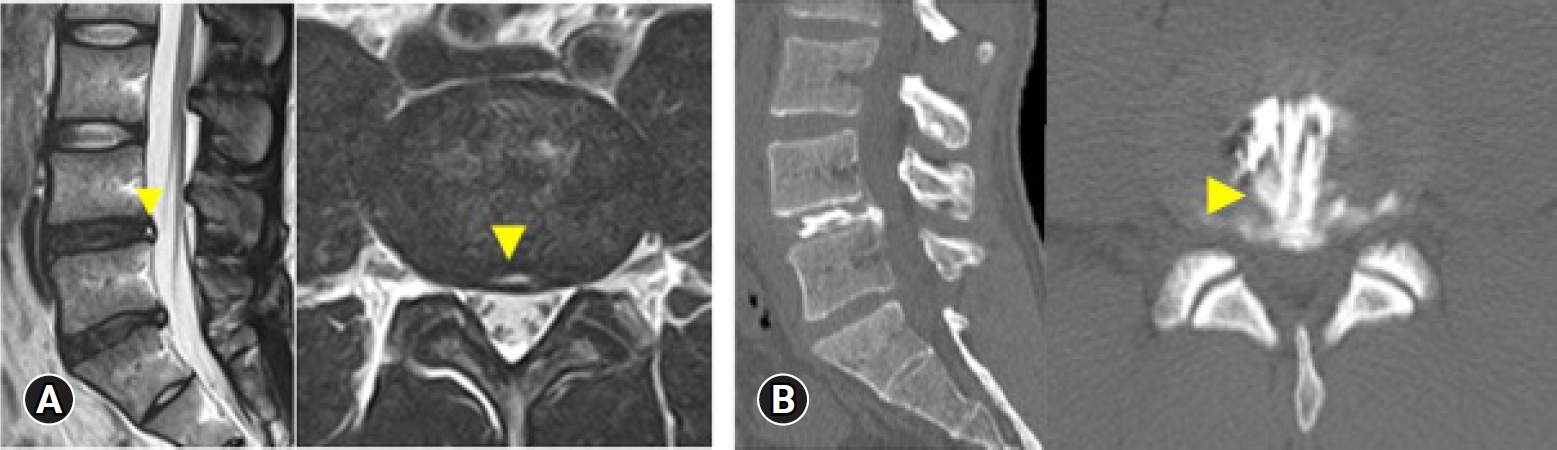

Professional athletes may also commonly present with chronic discogenic pain. Morimoto et al. [37] examined 32 professional baseball players with low back pain and found that HNP was the most common cause of low back pain among those in their 20s (57%), whereas discogenic low back pain was the most common among those in their 30s (55%). For chronic discogenic low back pain, radiofrequency thermal annuloplasty (TA) with the TF-FESS technique (FESS-TA) is the most suitable minimally invasive intervention. The procedure was first reported by Tsou et al. [20] in 2004. In the first report of FESS-TA outcomes in top-class athletes by Sairyo et al. [21] in 2013, good clinical outcomes were reported in all 4 cases. In 2019, Manabe et al. [22] reviewed 12 patients who had undergone FESS-TA and found 10 had an early RTS within 3 months (mean, 2.8 months) with full resolution of the chronic low back pain. The 2 remaining patients underwent additional surgery and ultimately returned to their previous competitive level. Taken together, these findings indicate that FESS-TA can be an effective minimally invasive intervention even for top-class athletes. Figure 5 shows the imaging findings of a professional soccer player who had been experiencing chronic low back pain for 1 year, recalcitrant to conservative treatment. The MRI scans clearly show a high signal intensity zone [38], and CT-discograms show an obvious toxic annular tear [39]. His pain was almost fully resolved immediately after the FESS-TA, and he had an early RTS that same season.

Imaging findings in a male professional soccer player. MRI clearly indicates a high signal intensity zone (A; arrows), and CT-discography reveals an obvious toxic annular tear (B; arrow). MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography.

Kamada et al. [34] reported a pathology unique to athletes, radicular symptoms due to lumbar foraminal stenosis at the right L5-s level, in a professional baseball player. The left-handed pitcher showed right-sided facet hypertrophy, which had led to the foraminal stenosis and L5 radiculopathy. Full-endoscopic lumbar foraminotomy was performed during the off-season, and immediately after the surgery the symptoms disappeared. The pitcher had an early RTS the following season.

Maeda et al. [35] reviewed 5 professional baseball players who underwent TF-FESS. Three players who underwent the surgery during the off-season had an early RTS at the beginning of the following season. The remaining 2 players who underwent surgery just before the beginning of the next season and both returned about 1 month after the season started. TF-FESS for athletes is considered the best option for athletes to make a faster RTS.

3. Suitability in the Elderly With Poor General Health

Lumbar spinal canal stenosis (LSS) is a lumbar disorder that affects the elderly. There are 3 types of LSS [40], foraminal, lateral recess, and central. Decompression of LSS requires general anesthesia when performing IL-FESS but only local anesthesia when performing TF-FESS.

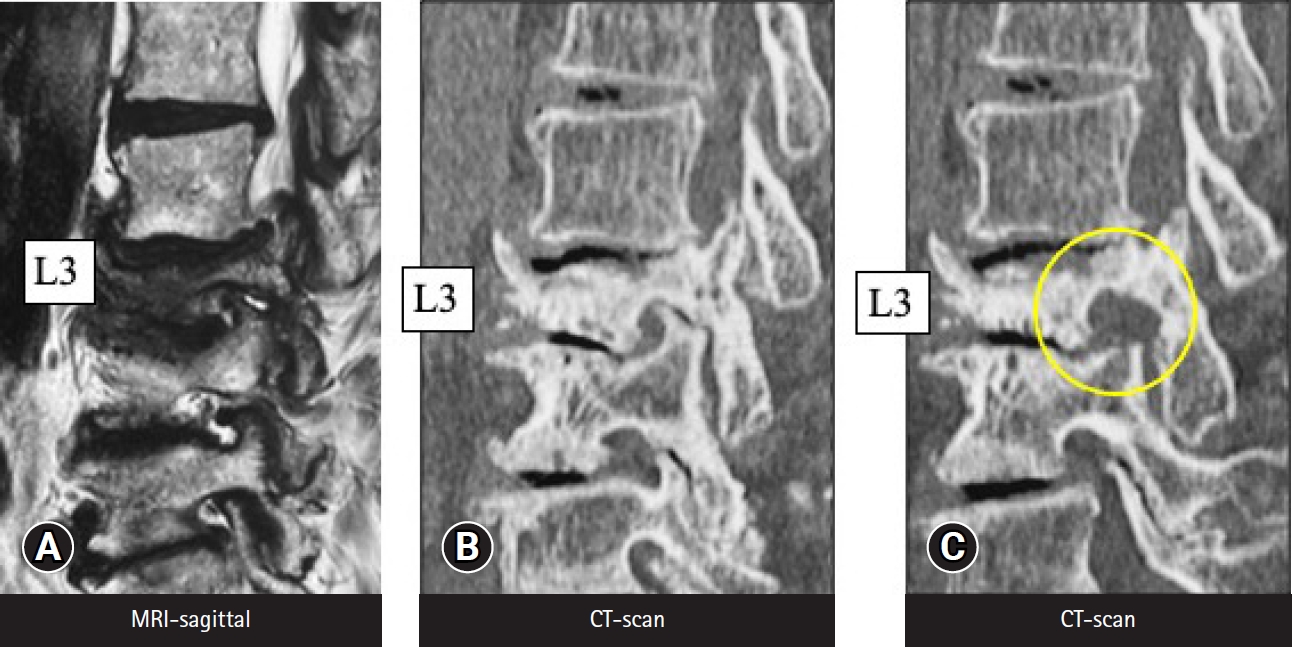

Taking the first of these 3 types, foraminal decompression for foraminotomy is the best indication for TF-FESS because the foraminal area is anatomically the easiest to access. There are many clinical reports of foraminotomy under the local anesthesia [3,41-44]. Figure 6 shows MRI and CT scans before and after full-endoscopic foraminotomy performed under local anesthesia in an 89-year-old woman, because her cardiac condition and advanced age were contraindications for general anesthesia. The foraminal area was increased by bony decompression (Figure 6). Yeung and Gore [3] have also emphasized the clear merits of TF-FESS for revision surgery following posterior decompression. The IL space would be filled with scar tissue following posterior surgery, and IL revision surgery may require fusion surgery. TF-FESS, on the other hand, can access the foramen directly, thereby avoiding fusion surgery. Yagi et al. [45] came to a similar conclusion based on an analysis of 48 patients who underwent TF-FESS for revision surgery. Clinical outcomes were excellent or good in 73.4% of cases and fusion surgery could be avoided.

MRI (A) and CT scans before (B) and after (C) full-endoscopic foraminotomy performed under local anesthesia, in an 89-year-old woman. Her cardiac condition and advanced age were contraindications for general anesthesia. (C) The circle in the right panel indicates the enlarged foraminal area after the surgery. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography.

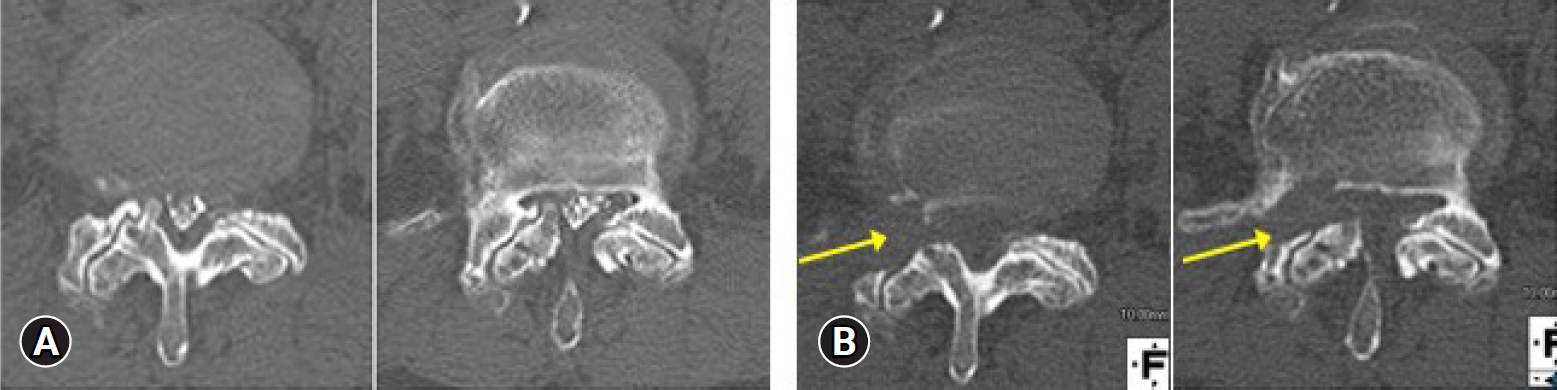

Lateral recess stenosis is the next most relevant indication for TF-FESS anatomically. A novel procedure for treating lateral recess stenosis was reported by Sairyo et al. [46] in 2017. The procedure was called ventral facetectomy, since almost all of the ventral half of the facet joint is resected [46,47]. Figure 7 shows a typical CT scan before and after ventral facetectomy in which the ventral side of the facet is removed under local anesthesia. In addition, Hashimoto et al. [48] reported a very interesting case involving an elderly patient in poor general health who complained of pain in both legs, which was due to bilateral lateral recess stenosis at L3–4 and L4–5. They decided to perform a 4-stage operation because decompression was needed at the 4 stenotic sites. Leg pain was decreased after the surgery and the patient could move his leg by himself. Figure 8 shows the MRI findings before full-endoscopic ventral facetectomy in atypical case. The right panel in Figure 8 clearly indicates the decompressed L5 nerve root. In another study, Kishima et al. [12] clinically reviewed 85 cases of full-endoscopic ventral facetectomy. They concluded that favorable clinical outcomes were obtained overall, but were not satisfactory in cases of instability or scoliosis.

Typical computed tomography (CT) findings before (A) and after (B) ventral facetectomy. The ventral side of the facet was removed (arrows) under local anesthesia.

(A) Magnetic resonance image findings before the ventral facetectomy in a 90-year-old man with L4–5 lateral recess stenosis. (B) Full-endoscopic ventral facetectomy was performed and the decompressed L5 nerve root is shown on the right panel.

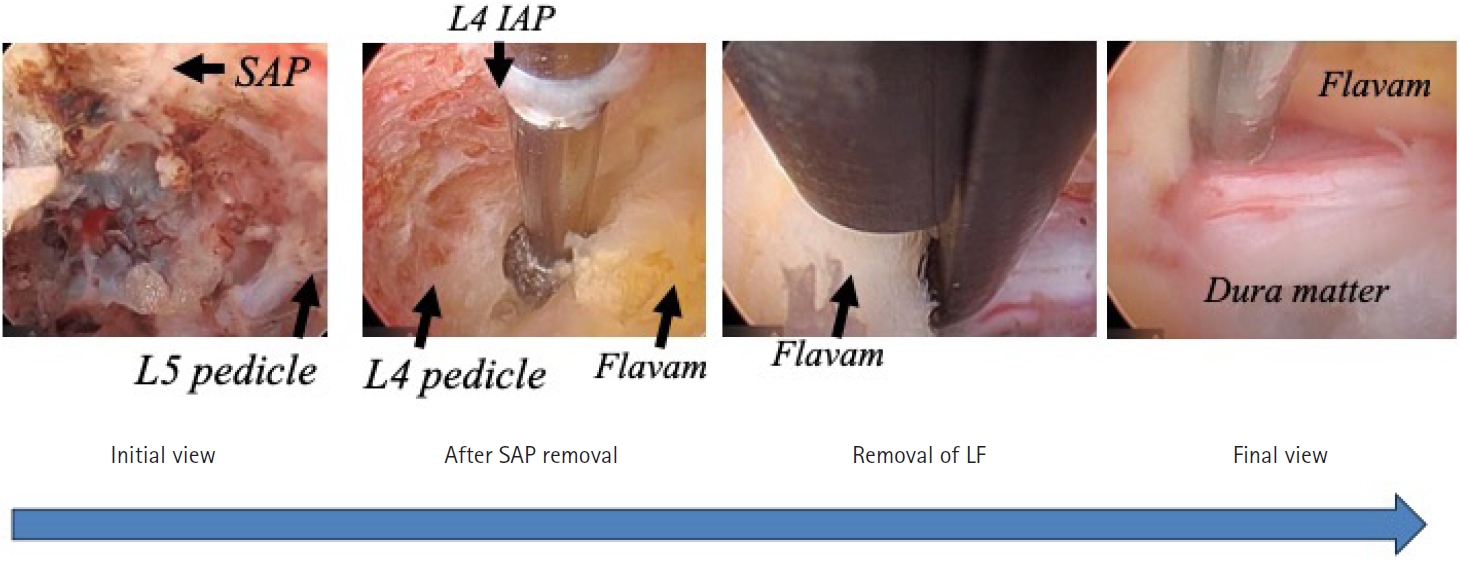

The final challenge was full-endoscopic decompression of central canal stenosis. Basically, in the patients with central stenosis, posterior laminectomy and complete removal of the thick ligamentum flavum should be done under the general anesthesia. However, surgery under general anesthesia is contraindicated in elderly patients with central stenosis and poor general health. Thus, the technique of full-endoscopic lumbar undercutting laminectomy (LUL) was developed [11]. Although complete decompression is difficult with full-endoscopic LUL, partial recovery and partial alleviation of the pain is possible. Figure 9 shows imaging findings in a 88-year-old woman with central canal stenosis and poor general health. She had been taking steroids and having home oxygen therapy for more than 1 year to treat pulmonary fibrosis. She could not stand for 1 minute. Also, she could not walk because of severe pain in both legs, especially the left leg. General anesthesia was contraindicated and therefore two-stage full-endoscopic LUL under local anesthesia was planned for the left and right sides. Because the left leg pain was severe, left LUL was performed first. CT scans after the surgery showed the osseous tissue removed, and MRI scans showed an enlarged neural canal (Figure 9). Figure 10 shows the endoscopic view during surgery. The superior articular process was removed first, followed by LUL. The thick ligamentum flavum was exposed and then removed. Finally, the dura matter was exposed and pulsation of the dural sac was observed for confirmation of sufficient decompression.

MRI (A, C) and CT (B, D) findings before and after full-endoscopic LUL in an 88-year-old female with central canal stenosis and in poor general health. LUL was first conducted for the left side. (D) The CT scan after surgery indicates the osseous tissue removed, and MRI (C) shows an enlarged neural canal. The circle indicates the change in the dural tube, and it increased after the surgery. The arrow demonstrates the area of bone removal. Undercutting laminectomy is conducted after the surgery. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography; LUL, lumbar undercutting laminectomy.

Endoscopic views during surgery in the patient shown in Figure 9. First, the superior articular process was removed, followed by lumbar undercutting laminectomy. When the thick ligamentum flavum was exposed, it was removed. Finally, when the dura matter was exposed, pulsation of the dural sac was observed for confirmation of sufficient decompression. IAP, inferior articular process; SAP, superior articular process; LF, ligamentum flabum.

There is a limitation of the full-endoscopic LUL surgery. As shown in Figure 9, decompression is not enough after the surgery. Thus, IL decompression should be suitable for the central stenosis [49,50]; however, IF surgery basically requires general anesthesia. In this reason, for the elderly patients with poor general condition, full-endoscopic LUL would be better so far. We may need to develop more appropriate surgical technique to adequately decompress the central stenosis under the local anesthesia.

CONCLUSION

TF-FESS is a minimally invasive procedure, especially when involving the back muscles, and it can be done under local anesthesia. Thus, the 3 key strengths and merits of TF-FESS are the following.

(1) Early RTW is possible.

(2) Athletes can have a faster return to sports at their previous competitive level.

(3) Elderly individuals at high risk because of poor general health can undergo TF-FESS.

These advantages will likely make TF-FESS the future gold standard in spine surgery.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.