INTRODUCTION

The disc herniation incidence at C2–3 level is relatively not that common when compared to that of its occurrence in the subaxial cervical spine. Therefore, early diagnosis can be difficult for the clinicians and there are high chances that this can go undiagnosed. Even after diagnosing a C2–3 disc herniation, many spine surgeons are relatively very inexperienced in performing any sort of minimally invasive surgery at this level as it can be very challenging. Various extensive and traumatic surgical techniques like the Cloward’s technique [1], transoral odontoidectomy with or without occipitocervical fusion [2,3], anterior discectomy with fusion [2,4], far lateral approach [1,5], posterior transdural approach [6-8], anterolateral extradural approach [9] have been used to address the C2–3 disc herniation. Since these described techniques are very extensile and destructive ones, so a lot of disadvantages goes with it. Hence, we herein report a safe and minimally invasive procedure in the form of posterior cervical unilateral biportal endoscopic foraminotomy technique for addressing the C2–3 foraminal disc herniation.

CASE REPORT

1. History

A 62-year-old female presented in the outpatient clinic of our hospital with complaints of 6 weeks duration posterior axial neck pain and sudden onset hypoesthesia over the right preauricular region, face and lip. The patient initially had relief of the posterior neck pain on taking analgesics and doing physiotherapy but later did not have any significant improvement. The intensity of the neck pain increased during the off period from analgesics and now even after taking analgesics there is no relief at all in her neck pain.

2. Examination

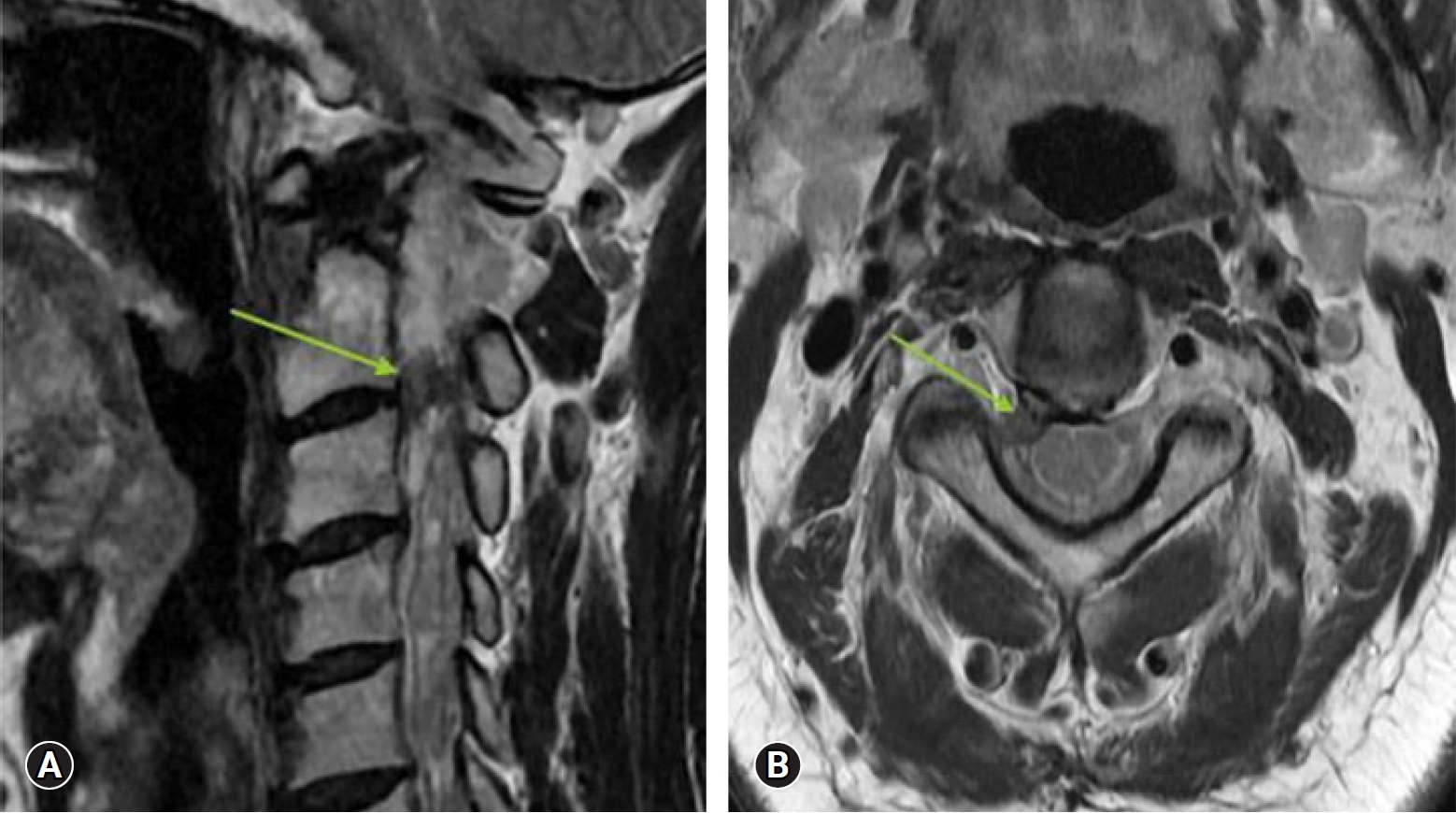

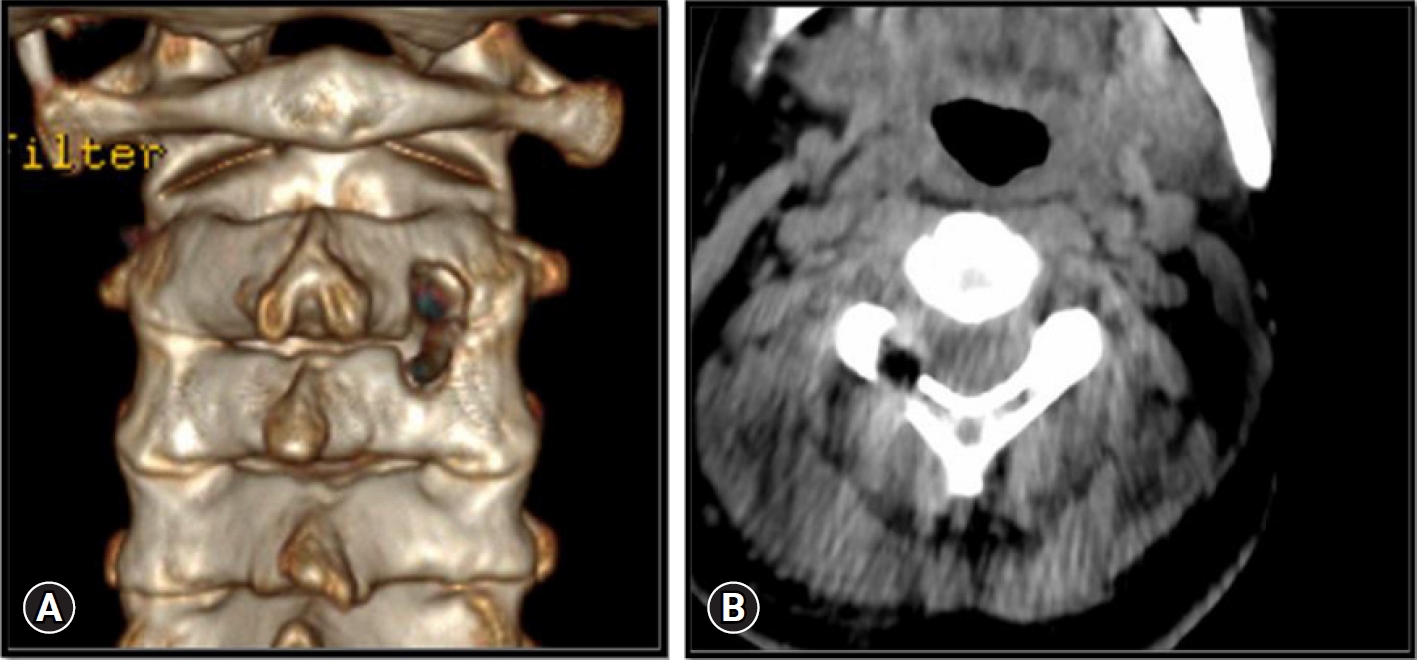

On performing neurological assessment, the patient was not able to move her head owing to the severity in pain. She was in complete distress as there was no resolution in the pain and her sleep was seriously affected for many days. All her neck movements were restricted due to pain but did not show any myelopathic symptoms or signs. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was normal but that of the cervical spine showed a C2–3 level foraminal disc herniation that was compressing the right C3 root (Figure 1) which indicated the need for surgery.

3. Surgical Technique

1) Equipment’s Used in Biportal Endoscopic Cervical Foraminotomy

*4.0-mm diameter zero-degree arthroscope

*4-mm solid diamond burr

*4-mm shaver with protective sleeve

*3.75-mm ninety-degree radiofrequency ablator and 1.4 mm thirty-degree micro ablator radiofrequency probe for controlling intraoperative bleeding

*Serial dilators

*Commonly used foraminotomy instruments like 1 mm & 2 mm Kerrison punches, 1.5 mm standard and upbite pituitary forceps, nerve hook (ball tip probe) and small curettes.

2) Surgical Steps

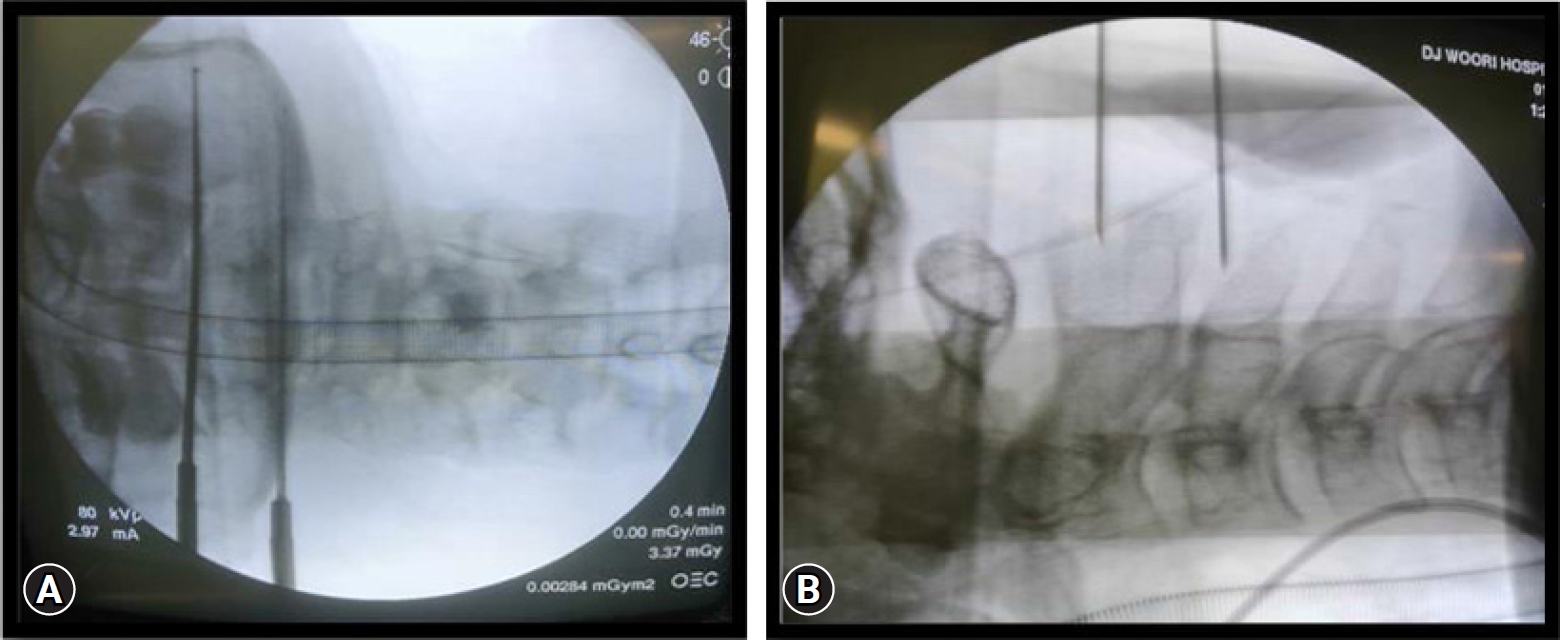

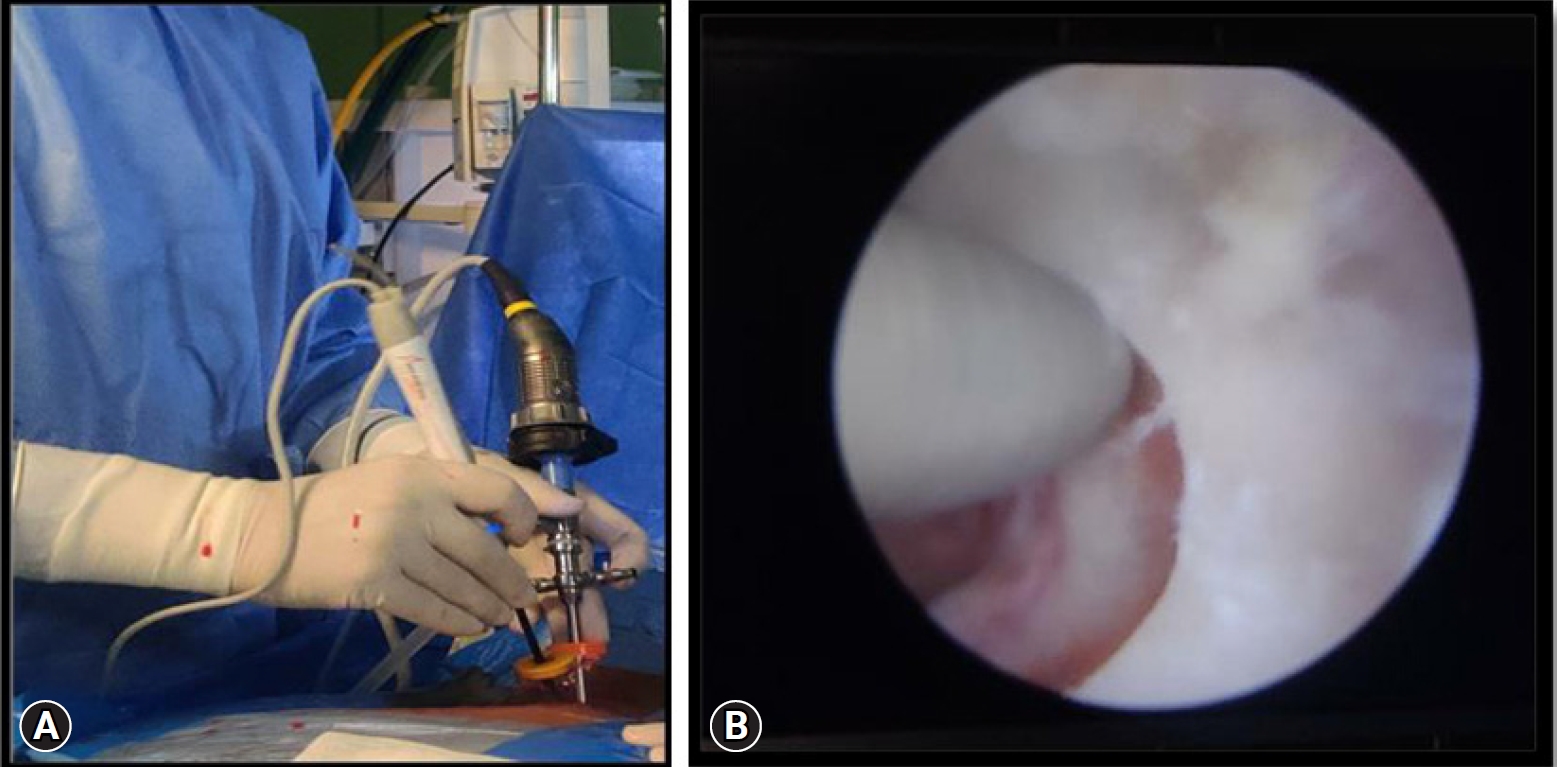

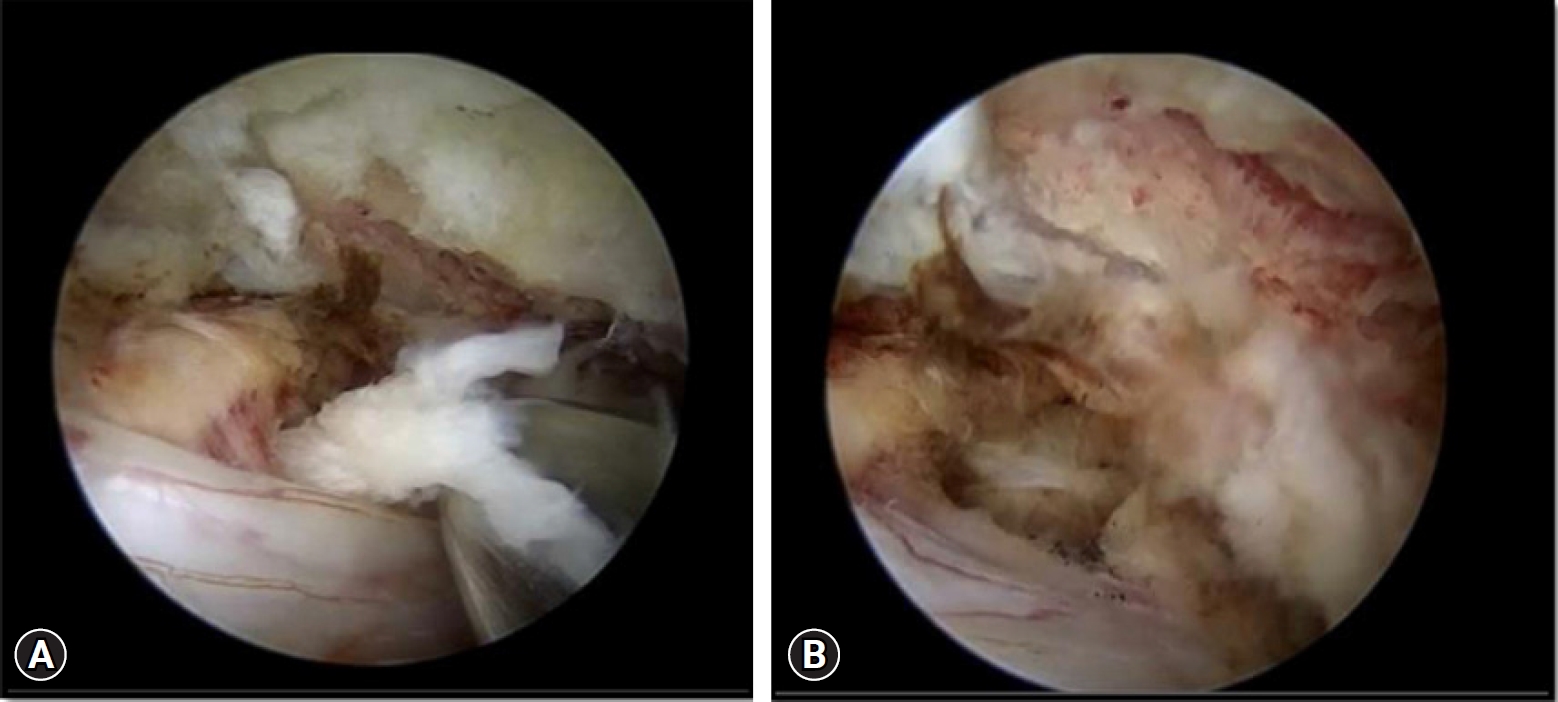

For the surgery, patient taken in prone position after giving general anesthesia. The H shaped pillow was used to relax the abdomen so as to avoid an increased abdominal pressure. The eye ball and face were protected from direct high pressure using a gel type facial pad. The neck kept in flexed position and upper back to the slanting down manner to get a good venous return and thereby reduces the chance of excessive intra operative bleeding. The head was fixed in flexed position and both the shoulders were pulled and fixed with a plaster tape. No head rest or any cervical traction kit was used. With strict aseptic precautions, sterile painting and draping of the entire posterior neck was done. Since the lesion was on the right side and the surgeon right handed, so the surgeon stood on the left side (Figure 2A). Under C-arm fluoroscopy guidance, C2 and C3 pedicles were marked (Figure 3). Each 0.5 cm long two transverse skin incisions each made along the marked pedicles. The caudal skin incision over the lower pedicle was for the working portal and the cranial skin incision over the cranial pedicle was for the scope portal. An approximate of 2 cm distance was kept between both the portals. In order to achieve the required operative space, serial dilators were used for neck muscle dissection. A cannula and then a zero-degree scope was inserted through it from the cranial scopic portal. A proper natural saline irrigation system through the operative area was confirmed. No saline pressure pump was used instead the height of the saline bag holding stand was kept at 1.6 m from the floor. Now, through the caudal working portal, surgical instruments were inserted. After triangulation of the instruments and endoscope at the target V point (that is on the margin of the superior lamina, inferior lamina and the medial point of facet joint), the radiofrequency probe was used to clear the soft tissue remnants and control the minor bleedings. After thoroughly delineating the V-point, next is to drill out the portion of superolateral part of the lower lamina, inferolateral portion of the upper lamina (Figure 2B) and medial point of the facet joint (V-point) using a 4 mm diamond burr. It was done until ligamentum flavum of caudocranial margin was exposed. The ligament flavum was preserved throughout the drilling for laminotomy to protect the neural structure beneath. The burr was then directed laterally for foraminotomy to the inner surface of the facet joint along direction of the root. By using a 1 mm, 2 mm Kerrison punches and small curettes, distal portion of the root can be further decompressed by removing the cranial tip of the SAP (superior articular process). Now after achieving enough bony decompression, the yellow ligament was removed from the thecal sac by piecemeal method along the direction of root. The small 1.4 mm thirty-degree radiofrequency ablator was used to achieve complete hemostasis around the root origin. Once a clear field was achieved, the adequacy of decompression confirmed by passing a nerve hook or ball tip probe through the foraminal canal without any resistance. Discectomy/fragmentectomy now performed using the nerve hook and pituitary forceps (Figure 4A). The cannula of the scope can be used as a protection for the root while performing this discectomy. Root is checked finally for complete decompression (Figure 4B), hemostasis confirmed and wound closed over subcutaneous suture and skin suture with hemovac drain in situ. The patient was kept on a soft neck collar for 2 weeks.

DISCUSSION

It is believed that intervertebral disc herniation results because of a long-term degenerative process happening in the disc. This C2–3 disc herniation is a rare case [7,10] since according to the present literatures available, there is less than 1% of incidence [10] and management of the same by posterior cervical foraminotomy by biportal endoscopic technique has not been described anywhere. The levels C5–6 and C6–7 are the commonly involved levels as there is maximum mobility at these lower segments and are therefore subjected to increased stress during movements. As the age of the patient increases, there occurs both bone and discal remodeling respectively which results in lower level disc fusion, decreased mobility of that segments and subsequently the load distribution to upper levels like C2–3 and C3–4 disc increases [7]. This contributes to the mean occurrence of C2–3 disc herniation in elderly population [11,12]. There can be varying clinical presentations in the background of degenerative damage as its a late onset from a mere sensory or motor radiculopathy to a severe myelopathy or even Brown Sequard syndrome [4,10,11,13].

In this case, the patient did not have any classical radicular symptoms of nerve root compression instead the patient presented with not improving posterior axial neck pain of almost 6 weeks duration and sudden onset of right side periauricular, lip and face hypoesthesia.

The patient was put initially on oral analgesics and steroid medications along with physiotherapy by other treating physicians since the onset of neck pain. Since the patient did not have any significant improvements in the symptom during the off period from medications and as a part of our treatment protocol to diagnose the underlying pathology, MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) of the cervical spine was done which showed a C2–3 disc herniation of foraminal type compressing the C3 nerve root. As the conservative trials did not yield any promising results, a surgical intervention was planned to give a better outcome. The most commonly practiced surgical procedures were ACDF (anterior cervical discectomy and fusion) and PCF (posterior cervical foraminotomy). Since we wanted to offer a safe and less traumatic procdure, a minimally invasive endoscopic technique with a biportal approach to conventional arthroscopic systems for spinal disease [14,15] was opted to decompress the C3 nerve root.

The rationale for choosing this approach was that a direct access could be gained to the foraminal lesion site thereby not needing to do an extensive discectomy, preserving the movement and major portion of the intervertebral disc. Since this is not a fusion procedure, so the graft related complications are avoided and reduces the chance of adjacent segment disease. This minimally invasive cervical foraminotomy is also a better cost effective procedure than ACDF [16]. Since this biportal endoscopic surgery is carried out completely under a continuous fluid irrigation, this decreases the chance of intraoperative bleeding and also provides a clear, magnified, three dimensional vision of the operative field by the use of endoscope. This enables the operating surgeon to perform meticulous and fine manipulation around the neural structures safely. The use of radiofrequency probe also helps in significant reduction of epidural bleeding which usually creates a lot of trouble for the operating surgeon in a conventional open surgery. The second portal or the working portal allows an unconstrained, free use of various required surgical instruments thereby contributing to a better result. The other advantage of this procedure is that only targeted minimal bone resection (Figure 5) is needed and helps in achieving the clinical results comparable to that of the conventional procedures, while giving all the advantages of a minimally invasive procedure. This biportal endoscopic procedure enables a short surgical time, minimal surgical scar, rapid rehabilitation, short hospital stay, low postoperative care cost, early return to previous routine work and high patient acceptance [17]. However, the disadvantage for this technique is that it may not be helpful in addressing case of cervical instability, central canal stenosis and disc space collapse which calls for an anterior surgery for height restoration. This techniques also has a steep learning curve which needs time to master. The conventional open procedures expertise is very much needed in the field of spinal surgery and must be mastered by surgeons so that they can tackle the problems of limited possibility to expand the surgery in the event of an unforeseen obstacles and complications which may be faced when performing full endoscopic procedures.

In the year 1996, first case of unilateral biportal endoscopic (UBE) technique was reported for treatment of lumbar discectomy [18] and the clinical results of it were published two years after in 1998 [19]. Nowadays, all spine pathologies can be addressed with this full endoscopic biportal technique similar to a conventional open method.

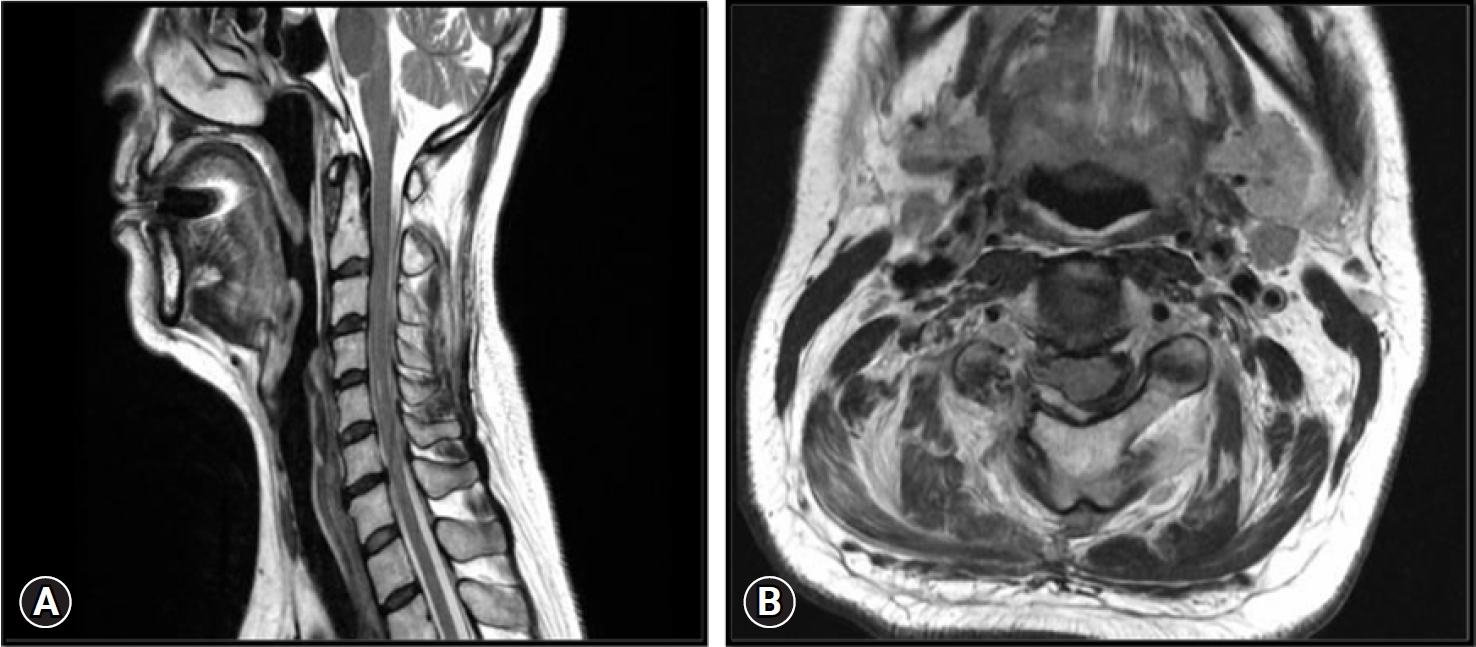

Postoperative radiological study (Figure 6) showed successfully removed protruded disc fragment and enlargement of the foraminal area significantly without the stability of the cervical spine being compromised. On two months clinical follow up after surgery, the patient has no neck pain and almost 50% recovery of the periauricular, lip and facial hypoesthesia. This case report shows that posterior biportal endoscopic foraminotomy technique is a good option for managing cervical foraminal disc herniation and foraminal stenosis. A long-term duration of follow up with more number of cases is indeed necessary to confirm the final outcomes.